|

|

- Search

| J Environ Anal Health Toxicol > Volume 26(2); 2023 > Article |

|

ABSTRACT

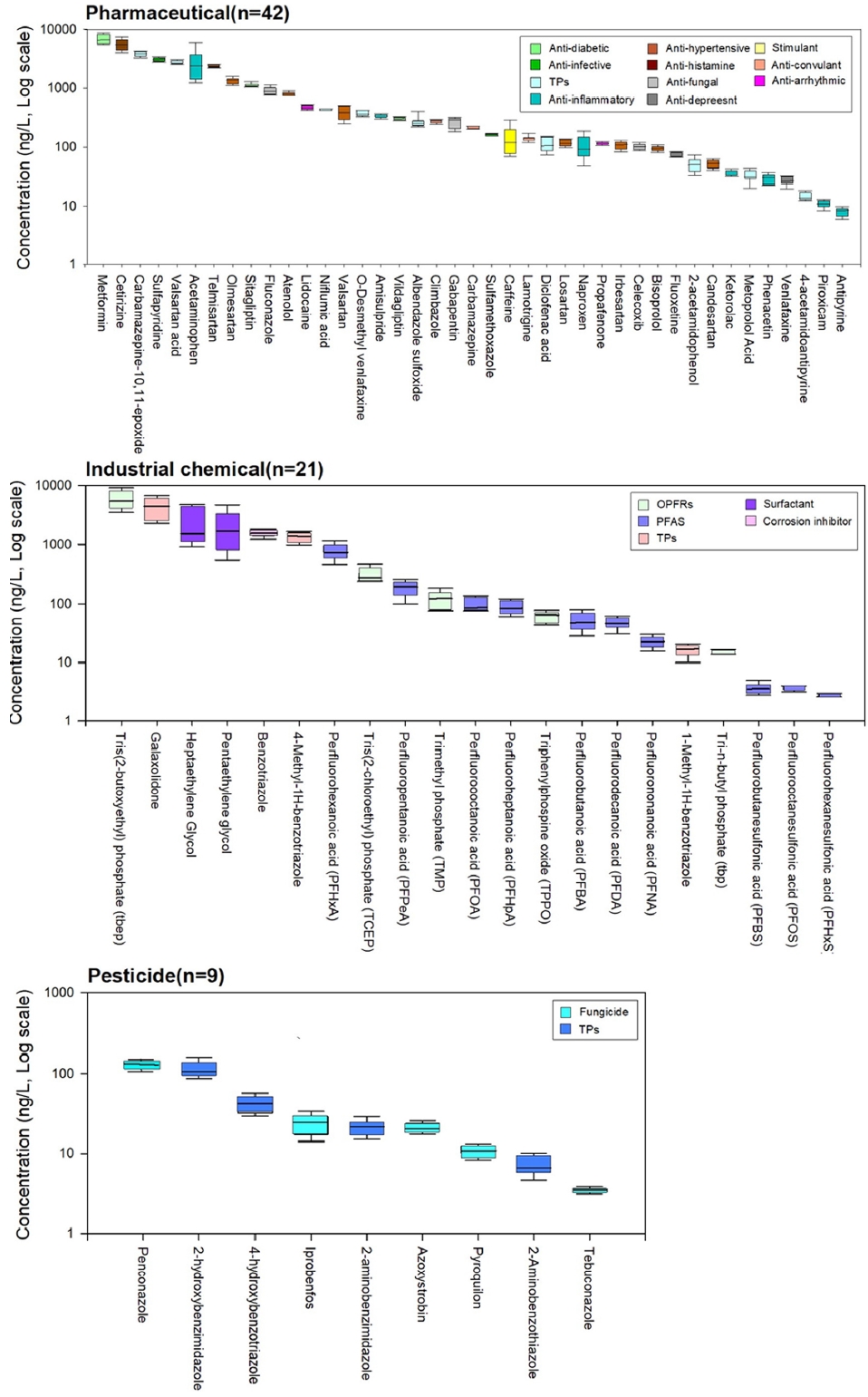

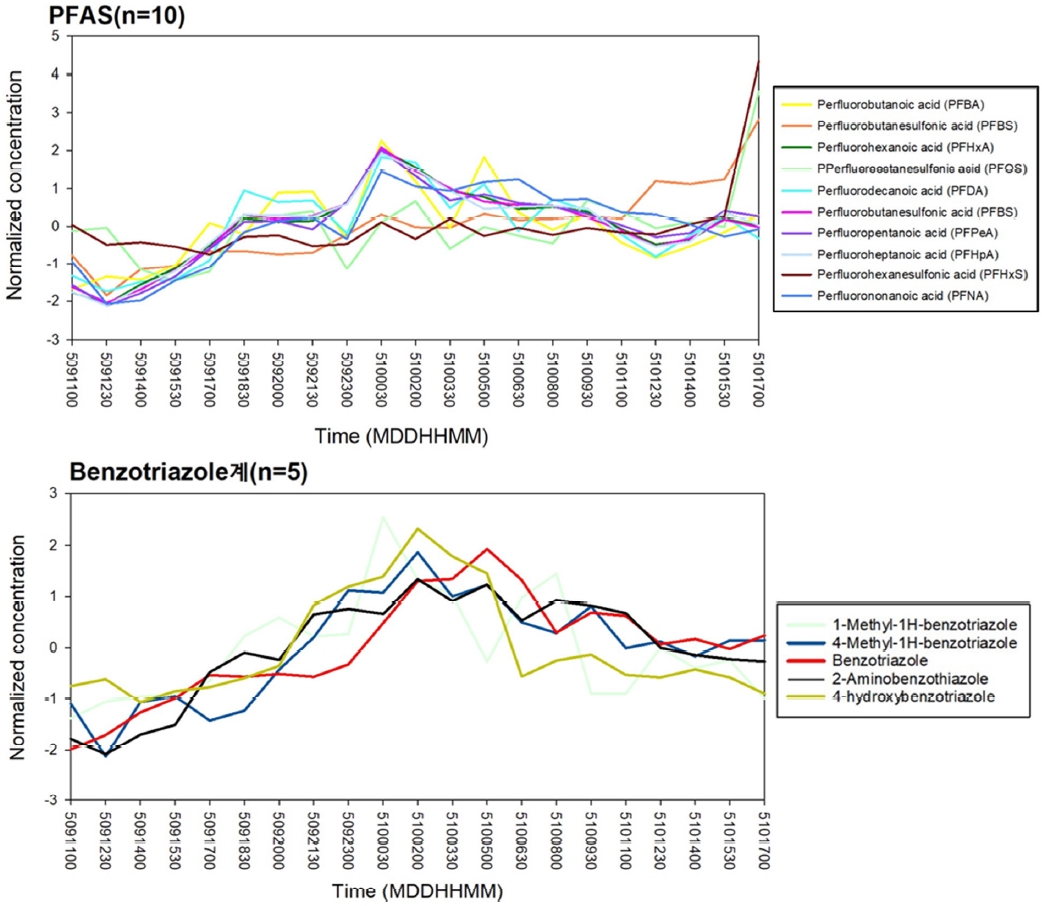

With the increase of manufacturing and use of chemicals, an increasing amount of chemicals enters surface water through various pathways. Their concentrations range from ng/L to mg/L, and they are recognized as micropollutants that pose potential risks to human health and aquatic ecosystems. This study quantitatively analyzed the diverse micropollutants in a stream affected by effluents from a waste-water treatment plant (WWTP) and demonstrated the changes in concentration over time. To capture temporal trends, water samples were collected using a portable composite sampler. For a comprehensive chemical analysis of the 148 species, target screening was conducted using liquid chromatography with high resolution mass spectrometer (LC-HRMS). As a result of the quantitative analysis, a total of 71 substances were detected at concentrations higher than the limit of quantification (LOQ). Pharmaceuticals accounted for the highest proportion among the detected substances. Tris (2-butoxyethyl) phosphate (tbep), which is used as an organophosphate flame retardant (OPFRs), was detected as a major pollutant at a maximum of 14,000 ng/L. Metformin, Pentaethylene glycol, cetirizine, galaxolidone, acetaminophen, heptaethylene glycol, carbamazepine-10,11-epoxide, sulfapyridine, valsartan acid, telmisartan, fluconazole, benzotriazole, olmesartan, 4-Methyl-1H-benzotriazole, sitagliptin, and perfluorohexanoic acid (PFHxA) were detected at concentrations of 1,000 ng/L or higher. As a unique temporal trend in the concentration, per-and polyfluoroalkyl substances (PFAS) and benzotriazoles exhibited the highest concentrations from 00:30 to 02:00 on 5/10 with a gradual decrease thereafter. The main factor responsible for this change in concentration was the effluent from the WWTP located upstream of the sampling point. In addition, the substance used in a nearby large-scale industrial complex is considered a significant factor.

ĻĖ░ņłĀņØś ļ░£ņĀäĻ│╝ ņØĖĻĄ¼ ļ░Å ņé░ņŚģ ĒÖ£ļÅÖņØś ņ”ØĻ░ĆņŚÉ ļö░ļØ╝ ņłśļ¦ÄņØĆ ĒÖöĒĢÖļ¼╝ņ¦łņØ┤ ņĀ£ņĪ░ ļ░Å ņāØņé░ļÉśĻ│Ā ņ׳ņ£╝ļ®░ Ēśäņ×¼ European Chemicals Agency (ECHA)ņŚÉ ļō▒ļĪØļÉ£ ĒÖöĒĢÖļ¼╝ņ¦łņØś ņłśļŖö ņĢĮ 22ļ¦īņóģņŚÉ ņØ┤ļźĖļŗż. ĒÖöĒĢÖļ¼╝ņ¦łņØś ņé¼ņÜ®ļ¤ēņØ┤ ņ”ØĻ░ĆĒĢ©ņŚÉ ļö░ļØ╝ ļŗżņ¢æĒĢ£ Ļ▓ĮļĪ£ļź╝ ĒåĄĒĢ┤ ņ¦ĆĒæ£ņłś, ļīĆĻĖ░ ļ░Å ĒåĀņ¢æ ļō▒ņØś ĒÖśĻ▓Įņ£╝ļĪ£ ļ░░ņČ£ļÉśĻ│Ā ņ׳ļŗż. ņ¦ĆĒæ£ņłś ļé┤ ļ░░ņČ£ļÉ£ ļ»Ėļ¤ēņśżņŚ╝ļ¼╝ņ¦łņØĆ ng/L ~ mg/LņØś ļåŹļÅä ļ▓öņ£äļĪ£ ņĪ┤ņ×¼ĒĢśĻ│Ā, ņØśņĢĮĒÆł, ļåŹņĢĮ, ņé░ņŚģņÜ®ņĀ£ ļō▒ņØś ļŗżņ¢æĒĢ£ ĒÖöĒĢÖļ¼╝ņ¦łņØä ĒżĒĢ©ĒĢ£ļŗż. ņ¦ĆĒæ£ņłś ļé┤ ņĪ┤ņ×¼ĒĢśļŖö ļ»Ėļ¤ēņśżņŚ╝ļ¼╝ņ¦łņØś Ļ▓ĮņÜ░ ļ¼╝ļ”¼ņĀü, ĒÖöĒĢÖņĀü, ņāØļ¼╝ĒĢÖņĀü ļ│ĆĒÖśĻ│╝ņĀĢņØä ĒåĄĒĢ┤ ļīĆņé¼ņ▓┤ (Transformation product, TPs)ļź╝ ĒśĢņä▒ĒĢśĻĖ░ļÅä ĒĢśļ®░, ņØ┤ļŖö ņāłļĪ£ņÜ┤ ĒÖśĻ▓ĮņśżņŚ╝ņøÉņ£╝ļĪ£ ņĢīļĀżņĀĖ ņ׳ļŗż. ņ¦ĆĒæ£ņłś ļé┤ ļ»Ėļ¤ēņśżņŚ╝ļ¼╝ņ¦łņØś ņŻ╝ņÜö ļ░░ņČ£ņøÉņØĆ ĒĢśĒÅÉņłśņ▓śļ”¼ņןņ£╝ļĪ£ ņĢīļĀżņĀĖ ņ׳ļŗż[1,2,3,4]. ĒĢśĒÅÉņłśņ▓śļ”¼ņןņØś ņØ╝ļ░śņĀüņØĖ ņ▓śļ”¼ļ░®ņŗØ (e.g., ņāØļ¼╝ĒĢÖņĀüņ▓śļ”¼ ļō▒)ņ£╝ļĪ£ļŖö ņ╣£ņłśņä▒ ļ░Å ļé£ļČäĒĢ┤ņä▒ ĒŖ╣ņä▒ņØä ņ¦ĆļŗłļŖö ļīĆļČĆļČäņØś ņØśņĢĮĒÆł, ļåŹņĢĮ ļ░Å ņé░ņŚģņÜ®ņĀ£ņÖĆ Ļ░ÖņØĆ ņ£ĀĻĖ░ĒÖöĒĢÖļ¼╝ņ¦łņØä ļČĆļČäņĀüņ£╝ļĪ£ ņ▓śļ”¼ĒĢśĻ▒░ļéś ņ▓śļ”¼ĒĢśņ¦Ć ļ¬╗ĒĢ£ ņ▒ä ņ¦ĆĒæ£ņłś ļé┤ļĪ£ ļ░®ļźśļÉśĻ│Ā ņ׳ļŗż[5]. ņ¦ĆĒæ£ņłśļĪ£ ņ£Āņ×ģļÉ£ ļ»Ėļ¤ēņśżņŚ╝ļ¼╝ņ¦łņØĆ ļ»Ėļ¤ēņØś ņłśņżĆņØ╝ņ¦ĆļØ╝ļÅä ņןĻĖ░Ļ░ä ļģĖņČ£ ņŗ£, ņØĖĻ░äņØś Ļ▒┤Ļ░Ģ ļ░Å ņłśņāØĒā£Ļ│äņŚÉ ļČĆņĀĢņĀüņØĖ ņśüĒ¢źņØä ļ»Ėņ╣Ā ņłś ņ׳ņ¢┤ ĻŠĖņżĆĒĢ£ ļ¬©ļŗłĒä░ļ¦ü ļ░Å ņĀĆĻ░ÉļīĆņ▒ģņØ┤ ĒĢäņÜöĒĢ£ ņŗżņĀĢņØ┤ļŗż.

ņ¦ĆĒæ£ņłś ļé┤ ņĪ┤ņ×¼ĒĢśļŖö ļ»Ėļ¤ēņśżņŚ╝ļ¼╝ņ¦ł ļČäņäØņØä ņ£äĒĢ£ ņŗ£ļŻī ņ▒äņĘ© ļ░®ņŗØņØĆ ņŗ£ļŻīņØś ĒŖ╣ņä▒ņŚÉ ļö░ļØ╝ ļŗ¼ļ”¼ ņØ┤ļżäņ¦Ćļ®░, ņØ╝ļ░śņĀüņ£╝ļĪ£ spot samplingņØ┤ļØ╝Ļ│Ā ļČłļ”¼ļŖö manual grab sampling ņØś Ļ▓ĮņÜ░, ĒŖ╣ņĀĢ ņāśĒöīļ¦ü ņ£äņ╣ś ļ░Å ņŗ£Ļ░ä ļśÉļŖö ņāśĒöīļ¦ü ņ£äņ╣ś ļé┤ ĒŖ╣ņĀĢ ņĀĢļ│┤ ļō▒ņØä ņøÉĒĢĀ ļĢī ĒÖ£ņÜ®ļÉ£ļŗż. ĒĢśņ¦Ćļ¦ī ĒÖöĒĢÖņé¼Ļ│ĀņÖĆ Ļ░ÖņØĆ ņĀæĻĘ╝ņØ┤ ņ¢┤ļĀżņÜ┤ Ļ▓ĮņÜ░ ļśÉļŖö ļīĆļ¤ēņØś ņŗ£ļŻīĻ░Ć ĒĢäņÜöĒĢ£ Ļ▓ĮņÜ░ņŚÉļŖö manual grab samplingņ£╝ļĪ£ ļČäņäØņØä ņ¦äĒ¢ēĒĢśĻĖ░ņŚÉļŖö ļ¦ÄņØĆ ĒĢ£Ļ│äĻ░Ć ņ׳ļŗż. ņØ┤ļź╝ ļīĆņ▓┤ĒĢśĻĖ░ ņ£äĒĢśņŚ¼ composite sampler ļ░Å passive sampler ļō▒ņØś ļŗżņ¢æĒĢ£ ņ▒äņĘ© ļ░®ļ▓ĢņØ┤ ļ░£ņĀäļÉśņ¢┤ ņÖöļŗż[6,7,8]. ĒŖ╣Ē׳, composite samplerļŖö ņāśĒöīļ¦ü ĻĖ░Ļ░äļÅÖņĢł ņØ╝ņĀĢĒĢ£ Ļ░äĻ▓®ņŚÉ Ļ▒Ėņ│É ņŗ£ļŻī ņ▒äņĘ©Ļ░Ć ņØ┤ļŻ©ņ¢┤ņ¦Ćļ®░, ņŗ£Ļ░ä Ļ▓ĮĻ│╝ņŚÉ ļö░ļźĖ ņŗ£ļŻīņØś ļåŹļÅä ļ░Å Ļ▓ĮĒ¢źņØä ĒīīņĢģĒĢĀ ņłś ņ׳ļŗż. ņŗżņĀ£ ņ¦ĆĒæ£ ņłśļŖö ļŗżņ¢æĒĢ£ ņĀÉņśżņŚ╝ņøÉ ļ░Å ļ╣äņĀÉņśżņŚ╝ņøÉņŚÉ ņØśĒĢ£ ņ£Āņ×ģņ£╝ļĪ£ ņŗ£Ļ░äĻ▓ĮĻ│╝ņŚÉ ļö░ļźĖ ļåŹļÅä ļ│ĆĒÖöĻ░Ć Ēü¼ļŗżĻ│Ā ĒīÉļŗ©ļÉ£ļŗż. ĒĢśĒÅÉņłśņ▓śļ”¼ņן ņØĖĻĘ╝ņŚÉ ņ£äņ╣śĒĢ£ ĒĢśņ▓£ņØś Ļ▓ĮņÜ░, ĒĢśĒÅÉņłśņ▓śļ”¼ņן ļ░®ļźśņŗ£Ļ░äņØ┤ ļ»Ėļ¤ēņśżņŚ╝ļ¼╝ņ¦ł ļåŹļÅä ļ│ĆĒÖöņŚÉ ņ£ĀņØśļ»ĖĒĢ£ ņśüĒ¢źņØä ļ»Ėņ│żņØä Ļ▓āņØ┤ļØ╝ ļ│┤ņŚ¼ņ¦Ćļ®░, portable composite samplerļź╝ ĒÖ£ņÜ®ĒĢśņŚ¼ ņ¦ĆĒæ£ņłś ļé┤ ņĪ┤ņ×¼ĒĢśļŖö ļ»Ėļ¤ēņśżņŚ╝ļ¼╝ņ¦łņØś ņŗ£Ļ░äņŚÉ ļö░ļźĖ ļåŹļÅä ļ│ĆĒÖö ļ░Å Ļ▓ĮĒ¢źņä▒ņØä ļ¬©ļŗłĒä░ļ¦üĒĢĀ ĒĢäņÜöĻ░Ć ņ׳ļŗż.

ļ»Ėļ¤ēņśżņŚ╝ļ¼╝ņ¦łļČäņäØņŚÉ ĒÖ£ņÜ®ļÉ£ Ļ│Āņä▒ļŖź ņĢĪņ▓┤Ēü¼ļĪ£ļ¦łĒåĀĻĘĖļלĒö╝ņÖĆ Ļ│ĀļČäĒĢ┤ļŖź ņ¦łļ¤ēļČäņäØĻĖ░ (Liquid Chromatography High Resolution Mass Spectrometry, LC-HRMS)ļŖö Ļ┤æļ▓öņ£äĒĢ£ ņ£ĀĻĖ░ņśżņŚ╝ļ¼╝ņ¦łņØä ņŗØļ│äĒĢśļŖöļŹ░ ņĄ£ņĀüĒÖöļÉ£ Ļ▓āņ£╝ļĪ£ ņĢīļĀżņĀĖ ņ׳ņ¢┤ ņĀĢļ░ĆĒĢ£ ļČäņäØņØä ņÜöĻĄ¼ĒĢśļŖö ĒÖśĻ▓Į ņŗ£ļŻī ļé┤ ļ»Ėļ¤ēņśżņŚ╝ļ¼╝ņ¦ł ļČäņäØņŚÉ ņÜ®ņØ┤ĒĢśļŗż[9,10,11,12,13,14]. ESI (Electrospray ionization) ņåīņŖżļź╝ ņØ┤ņÜ®ĒĢ£ ņØ┤ņś©ĒÖö ļ░®ļ▓ĢņØĆ ņ╣£ņłśņä▒ņØ┤ Ļ░ĢĒĢ£ ņØśņĢĮĒÆł, ļåŹņĢĮ ļō▒ņØś ļ»Ėļ¤ēņśżņŚ╝ļ¼╝ņ¦łņŚÉ ļīĆĒĢ£ ļåÆņØĆ ņØ┤ņś©ĒÖö ĒÜ©ņ£©ņØä ļ│┤ņŚ¼ņżĆļŗż[15]. Ļ│ĀļČäĒĢ┤ļŖźņ¦łļ¤ēļČäņäØĻĖ░ļź╝ ĒÖ£ņÜ®ĒĢ£ ļČäņäØņØĆ ļé«ņØĆ mass errorņÖĆ ļåÆņØĆ ļ»╝Ļ░ÉļÅäļź╝ ĻĖ░ļ░śņ£╝ļĪ£ ņŗĀĒśĖņĀĢļ│┤ļź╝ ņØĖņ¦ĆĒĢśņŚ¼ ļ¦ÄņØĆ ļ»Ėļ¤ēņśżņŚ╝ļ¼╝ņ¦łņŚÉ ļīĆĒĢśņŚ¼ ļ│┤ļŗż ņĀĢĒÖĢĒĢ£ ļÅÖņŗ£ļČäņäØņØ┤ Ļ░ĆļŖźĒĢśļŗż.

ļ│Ė ņŚ░ĻĄ¼ņŚÉņä£ļŖö portable composite samplerļź╝ ņØ┤ņÜ®ĒĢśņŚ¼ ņŗ£ļŻī ņ▒äņĘ©ļź╝ ņ¦äĒ¢ēĒĢ£ Ēøä, LC-HRMSļź╝ ņØ┤ņÜ®ĒĢ£ ņĀĢļ¤ēļČäņäØņØä ĒåĄĒĢ┤ ĒĢśĒÅÉņłśņ▓śļ”¼ņן ņØĖĻĘ╝ ņ¦ĆĒæ£ņłś ļé┤ ņĪ┤ņ×¼ĒĢśļŖö ļ»Ėļ¤ēņśżņŚ╝ļ¼╝ņ¦łņØś ļČäĒż ļ░Å ļåŹļÅäļź╝ ĒÖĢņØĖĒĢśĻ│Āņ×É ĒĢ£ļŗż. ņØ┤ņÖĆ ĒĢ©Ļ╗ś, ņŗ£Ļ░ä Ļ▓ĮĻ│╝ņŚÉ ļö░ļźĖ ņØ╝ļČĆ ļ»Ėļ¤ēņśżņŚ╝ļ¼╝ņ¦ł ĻĘĖļŻ╣ņØś ļåŹļÅä ļ│ĆĒÖö ļ░Å Ļ▓ĮĒ¢źņä▒ņØä ĒīīņĢģĒĢśĻ│Āņ×É ĒĢ£ļŗż.

ņŗ£ļŻīņ▒äņĘ©ļŖö 2022ļģä 5ņøö 9ņØ╝Ļ│╝ 10ņØ╝ ņØ┤ĒŗĆņŚÉ Ļ▒Ėņ│É ļīĆĻĄ¼Ļ┤æņŚŁņŗ£ņŚÉ ņ£äņ╣śĒĢ£ ņ¦äņ▓£ņ▓£ ņØĖĻĘ╝ ĻĄ¼ļØ╝ 2ĻĄÉņŚÉņä£ ņØ┤ļŻ©ņ¢┤ņĪīņ£╝ļ®░, Portable composite sampler (HACH, USA)ļź╝ ĒåĄĒĢ┤ ņØ╝ņĀĢĒĢ£ ņŗ£Ļ░ä Ļ░äĻ▓®ņØä ļæÉĻ│Ā ņ┤Ø 21ĒÜī ņłśĒ¢ēļÉśņŚłļŗż (Fig. 1). ĒĢ┤ļŗ╣ ņ¦ĆņĀÉņØĆ ņØĖĻĘ╝ņŚÉ ņä£ļČĆĒĢśņłśņóģļ¦Éņ▓śļ”¼ņןĻ│╝ ņä▒ņä£ņé░ņŚģļŗ©ņ¦Ć Ļ┤Ćļ”¼Ļ│Ąļŗ©ņØ┤ ņ£äņ╣śĒĢ┤ ņ׳ņ¢┤ ĒĢśĒÅÉņłś ļ░®ļźśņłśņØś ņ¦üņĀæņĀüņØĖ ņśüĒ¢źņØä ļ░øĻ│Ā ņ׳Ļ│Ā, ņØśņĢĮĒÆł ļ░Å Ļ░£ņØĖĻ┤Ćļ”¼ ņÜ®ĒÆł ļ┐Éļ¦ī ņĢäļŗłļØ╝ ņé░ņŚģļŗ©ņ¦ĆņŚÉņä£ ņé¼ņÜ®ļÉśļŖö ļŗżņ¢æĒĢ£ ĒÖöĒĢÖļ¼╝ņ¦łņØ┤ Ļ▓ĆņČ£ļÉśĻ│Ā ļåÆņØĆ ļåŹļÅäļĪ£ ņĀĢļ¤ēļÉ£ Ļ▓āņ£╝ļĪ£ ļéśĒāĆļé£ļŗż[16]. ņ▒äņĘ©ļÉ£ ņŗ£ļŻīļŖö ņĢäņØ┤ņŖżļ░ĢņŖżņŚÉ ļŗ┤Ļ▓© ņŗżĒŚśņŗżļĪ£ ņś«ĻĖ┤ Ēøä, ņĀäņ▓śļ”¼ ņĀäĻ╣īņ¦Ć 4oC ņØ┤ĒĢśņŚÉņä£ ļāēņן ļ│┤Ļ┤ĆĒĢśņśĆļŗż

ņŚ░ĻĄ¼ņŗż ļé┤ ļ│┤ņ£ĀĒĢ£ ļéÖļÅÖĻ░Ģ ņ¦ĆņŚŁņØś ņןĻĖ░ ļŹ░ņØ┤Ēä░ļ▓ĀņØ┤ņŖżļź╝ ĒåĄĒĢ┤ Ļ▓ĆņČ£ņØ┤ ņśłņāüļÉśļŖö 148ņóģņØä ļČäņäØ ļīĆņāüļ¼╝ņ¦łļĪ£ ņäĀņĀĢĒĢśņśĆļŗż. ļīĆņāüļ¼╝ņ¦łņØĆ ņØśņĢĮĒÆł 74ņóģ, ņé░ņŚģņÜ®ņĀ£ ļ░Å ĻĖ░ĒāĆ 42ņóģ, ļåŹņĢĮ 32ņóģņ£╝ļĪ£ ĻĄ¼ļČäļÉśņŚłļŗż. Ēæ£ņżĆņÜ®ņĢĪ ņĀ£ņĪ░ļź╝ ņ£äĒĢ£ Ēæ£ņżĆļ¼╝ņ¦łĻ│╝ ļé┤ļČĆĒæ£ņżĆļ¼╝ņ¦łņØĆ ļ¬©ļæÉ ņł£ļÅä 95% ņØ┤ņāüņØś ņ┤łĻ│Āņł£ļÅä ļ¼╝ņ¦łņØä Sigma-Aldrich (Missouri, USA), Toronto Research Chemicals(North York, Canada), Wellington Laboratories (Ontario, Canada), J.T. baker(New Jersey, USA) ļ░Å Fisher Scientific (Pittsburgh, USA)ņŚÉņä£ ĻĄ¼ņ×ģĒĢśņŚ¼ ņé¼ņÜ®ĒĢśņśĆļŗż. ļČäņäØņŚÉ ņé¼ņÜ®ļÉ£ Ēæ£ņżĆļ¼╝ņ¦ł ļ░Å ļé┤ļČĆĒæ£ņżĆļ¼Ėņ¦łņØś ĻĄ¼ļ¦żņĀĢļ│┤ļŖö Table 1ņŚÉ Ēæ£ĻĖ░ĒĢśņśĆļŗż. ņŚÉĒāäņś¼ņŚÉ ņÜ®ĒĢ┤ļÉ£ Ēæ£ņżĆņÜ®ņĢĪ (500 ļśÉļŖö 1,000 mg/L)ņØĆ ļČäņäØ ņĀäĻ╣īņ¦Ć ŌłÆ20oC ņ¢┤ļæÉņÜ┤ Ļ││ņŚÉņä£ ļ│┤Ļ┤ĆĒĢśņśĆļŗż.

ņŗ£ļŻīņØś ņĀäņ▓śļ”¼ ļ░®ļ▓ĢņØĆ Ļ│Āņāü ņČöņČ£ļ▓Ģ (Solid phase extraction; SPE)ņØä ņĀüņÜ®ĒĢśņśĆļŗż. 1 L ņŗ£ļŻīļź╝ Glass microfiber filter (GF5; 0.45 ╬╝m)ņŚÉ ņŚ¼Ļ│╝ņŗ£Ēé© Ēøä, ļé┤ļČĆĒæ£ņżĆļ¼╝ņ¦ł (Internal standard, ISTD) 100ng ļ░Å buffer (pH 7 ┬▒ 0.5) 80 ╬╝Lļź╝ ’ŠĀņŻ╝ņ×ģĒĢśņśĆļŗż. ļŗżņ¢æĒĢ£ ļ¼╝ļ”¼ĒÖöĒĢÖņĀü ĒŖ╣ņä▒ņØä Ļ░Ćņ¦ĆļŖö ļ¼╝ņ¦łļōżņØä ļČäņäØĒĢśĻĖ░ ņ£äĒĢ┤ņä£, 4ņóģļźśņØś ĒØĪņ░® ļ¼╝ņ¦ł OASIS HLB, Isolute ENV+, Strata X-AW ļ░Å Strata X-CWļĪ£ ņØ┤ļŻ©ņ¢┤ņ¦ä ļŗżņĖĄ SPE ņ╣┤ĒŖĖļ”¼ņ¦Ć (multi-layer cartridge)ļź╝ ņé¼ņÜ®ĒĢśņśĆļŗż. ņŗ£ļŻīļź╝ 5 ~10 mL/minņØś ņ£ĀņåŹņ£╝ļĪ£ ņ╣┤ĒŖĖļ”¼ņ¦ĆņŚÉ ĒØśļĀż ļ│┤ļéĖ Ēøä, ņŗ£ļŻī loadingņØ┤ ļüØļé£ ņ╣┤ĒŖĖļ”¼ņ¦ĆļŖö ņ╝ĆņØ┤ņŖż ņĢłņŚÉ Ļ│ĀņĢĢ ņ¦łņåīĻ░ĆņŖżļź╝ ļČäņé¼ĒĢśņŚ¼ 1ņŗ£Ļ░äļÅÖņĢł Ļ▒┤ņĪ░ņŗ£ņ╝░ļŗż. Ļ▒┤ņĪ░Ļ░Ć ņÖäļŻīļÉ£ ņ╣┤ĒŖĖļ”¼ņ¦ĆļŖö ņČöņČ£ņØä ņ£äĒĢ┤ ļæÉ Ļ░Ćņ¦Ć ņÜ®ļ¦żņØĖ ņĢīņ╣╝ļ”¼ ņÜ®ņĢĪ 6 mL (ethyl acetate/methanol 50 : 50 with 0.5%’ŠĀ ammonia) ļ░Å ņé░ņä▒ ņÜ®ņĢĪ (ethyl acetate/methanol 50 : 50 with 1.7% formic acid)ļź╝ ĒåĄĒĢ┤ ņČöņČ£ĒĢśņśĆļŗż. ņČöņČ£ ņÜ®ņĢĪņØĆ ņ¦łņåīļåŹņČĢĻĖ░(CHONGMIN TECH, Korea)ļź╝ ņØ┤ņÜ®ĒĢśņŚ¼ 35oCņŚÉņä£ 0.1 mLĻ╣īņ¦Ć ļåŹņČĢņŗ£Ēé© Ēøä, pure water/methanol (9 : 1)ņØä ņŻ╝ņ×ģĒĢśņŚ¼ 1 mLļĪ£ ņ×¼ĻĄ¼ņä▒ĒĢśņśĆļŗż. 1 mL ņŗ£ļŻīļŖö cellulose acetate filter (0.2 ╬╝m)ņØä ņØ┤ņÜ®ĒĢśņŚ¼ ņŚ¼Ļ│╝ĒĢ£ Ēøä, ļČäņäØņÜ® vialņŚÉ ļŗ┤ņĢä ĻĖ░ĻĖ░ļČäņäØ ņĀäĻ╣īņ¦Ć 4oC ļāēņןļ│┤Ļ┤ĆĒĢśņśĆļŗż.

ļīĆņāüļ¼╝ņ¦ł 148ņóģņŚÉ ļīĆĒĢ£ ļŗżņä▒ļČä ļÅÖņŗ£ļČäņäØ ņ£äĒĢ┤ LC-HRMSņØä ņé¼ņÜ®ĒĢśņśĆĻ│Ā, ĻĖ░ĻĖ░ļŖö Ultimate 3000 ultra high performance chromatography (Thermo Fisher scientific, USA)ņŚÉ HESIĻ░Ć Ļ▓░ĒĢ®ļÉ£ Q Exactive plus quadrupole Orbitrap mass spectrometry (Thermo Fisher scientific, USA)ļź╝ Ļ▓░ĒĢ®ĒĢśņŚ¼ ņé¼ņÜ®ĒĢśņśĆļŗż. ļ¼╝ņ¦łņØś ļČäļ”¼ņŚÉļŖö Xbridge C18 column (2.1 ├Ś 50 mm, particle size 3.5 ╬╝m)ņØä ņé¼ņÜ®ĒĢśņśĆĻ│Ā, ņØ┤ļÅÖņāüņ£╝ļĪ£ļŖö pure water with 0.1% formic acid (A)ņÖĆ methanol with 0.1 % formic acid (B)Ļ░Ć ņØ┤ņÜ®ļÉśņŚłļŗż. ņŗ£ļŻī ņÜ®ņĢĪņØś injection volumeņØĆ 10 ╬╝lņØ┤Ļ│Ā, ņ╗¼ļ¤╝ ņś©ļÅä 35oCņŚÉņä£ BņØś ļ╣äņ£©ņØä 10%ļĪ£ ņŗ£ņ×æĒĢśņŚ¼ 4ļČä ļÅÖņĢł 50%Ļ╣īņ¦Ć ņ”ØĻ░Ćņŗ£ĒéżĻ│Ā, 17ļČäĻ╣īņ¦Ć 95%ļĪ£ ņ”ØĻ░Ćņŗ£Ēé© Ēøä 25ļČäĻ╣īņ¦Ć ņ£Āņ¦ĆĒĢśņśĆļŗż. 25ļČä Ēøä columnņØś ĒÅēĒśĢ ņāüĒā£ ņ£Āņ¦Ćļź╝ ņ£äĒĢśņŚ¼ ņØ┤ļÅÖņāü BņØś ļ╣äņ£©ņØä 10%ļĪ£ ĻĖēĻ▓®Ē׳ Ļ░Éņåīņŗ£ņ╝£ 2ļČä ļÅÖņĢł ņ£Āņ¦Ćņŗ£ņ╝£ ņŻ╝ņŚłĻ│Ā, ņ┤Ø ļČäņäØņŗ£Ļ░äņØĆ 29ļČä ļÅÖņĢł ņØ┤ļŻ©ņ¢┤ņĪīļŗż. ņØ┤ ļÅÖņāüņØś ņ£ĀņåŹņØĆ 0.2 mL/minņ£╝ļĪ£ ņ£Āņ¦Ćņŗ£ņ╝░ņ£╝ļ®░, ļ¬©ļōĀ ņŗ£ļŻīļŖö positive ļ░Å negative modeņŚÉņä£ ļČäņäØļÉśņŚłļŗż. Capillary ņś©ļÅäņÖĆ spray voltageļŖö 320oC ļ░Å positive, negative modeņŚÉņä£ Ļ░üĻ░ü 3.8 kV, 3.0 kVļĪ£ ņäżņĀĢĒĢśņśĆļŗż. Column ovenņØś ņś©ļÅäļŖö 35oCļĪ£ ļ¦×ņČ░ņŻ╝ņŚłļŗż.

ņĀĢļ¤ēļČäņäØņØĆ ļé┤ļČĆĒæ£ņżĆļ▓Ģ (internal standard calibration)ņØä ņé¼ņÜ®ĒĢśņŚ¼ ņłśĒ¢ēļÉśņŚłņ£╝ļ®░, ļČäņäØļ░®ļ▓ĢņØś ņĀĢĒÖĢļÅäņÖĆ ņŗĀļó░ļÅä Ļ▓Ćņ”ØņØä ņ£äĒĢ┤ Ļ▓Ćļ¤ēĻ│ĪņäĀņØś ņ¦üņäĀņä▒Ļ│╝ Ļ▓ĆņČ£ĒĢ£Ļ│ä (LOD, limit of detection), ņĀĢļ¤ēĒĢ£Ļ│ä (LOQ, limit of quantification), ņĀłļīĆ ĒÜīņłśņ£© (Absolute Recovery) ļ░Å ņĀĢļ░ĆļÅäļź╝ Ļ▓Ćņ”ØĒĢśņśĆļŗż. Ļ▓ĆņČ£ĒĢ£Ļ│äņÖĆ ņĀĢļ¤ēĒĢ£Ļ│ä ĒÖĢņØĖņØĆ Ēü¼ļĪ£ļ¦łĒåĀĻĘĖļשņāüņŚÉņä£ ļéśĒāĆļé£ Ēö╝Ēü¼ņØś S/Nļ╣äņ£© (signal to noise ratio) ļź╝ ĒÖĢņØĖĒĢśņŚ¼ ņĖĪņĀĢĒĢśņśĆļŗż. S/Nļ╣äņ£© Ļ░ÆņØ┤ 3ņØ┤ņāüņØ╝ Ļ▓ĮņÜ░ Ļ▓ĆņČ£ĒĢ£Ļ│äļĪ£ ĒĢśņśĆņ£╝ļ®░ ņĀĢļ¤ēĒĢ£Ļ│äļŖö 10ņØ┤ņāüņ£╝ļĪ£ ņäżņĀĢĒĢśņśĆļŗż. 11ļŗ©Ļ│äņØś ļåŹļÅä ļ▓öņ£ä (0.1, 0.5, 1, 2, 5, 10, 20, 50, 70, 100, 200 ng/L)ņØś Ēæ£ņżĆņÜ®ņĢĪņŚÉ ļīĆĒĢśņŚ¼ 100 ngņØś internal standardļź╝ ņŻ╝ņ×ģĒĢśņŚ¼ Ļ▓Ćļ¤ēĻ│ĪņäĀņØä ņ×æņä▒ĒĢśņśĆļŗż.

ņĀĢļ¤ēļČäņäØņØä ņ£äĒĢ£ Ļ▓ĆņĀĢĻ│ĪņäĀņØś ņ¦üņäĀņä▒ņØä ļéśĒāĆļé┤ļŖö R2 Ļ░ÆņØĆ ļ¬©ļōĀ ļīĆņāüļ¼╝ņ¦łņŚÉ ļīĆĒĢśņŚ¼ 0.99 ņØ┤ņāüņ£╝ļĪ£ ļéśĒāĆļé¼ņ£╝ļ®░, ļČäņäØņØś ņĀĢļ░ĆļÅäļź╝ ĒÖĢņØĖĒĢśĻĖ░ ņ£äĒĢ£ ņāüļīĆĒæ£ņżĆĒÄĖņ░©Ļ░Æ (Relative standard deviation, RSD)ņØĆ 25.0% ņØ┤ļé┤ņØś ņżĆņłśĒĢ£ ņłśņżĆņ£╝ļĪ£ ĒÖĢņØĖļÉśņŚłļŗż. Ļ▓ĆņČ£ĒĢ£Ļ│ä (LOD)ļŖö 123ņóģņØś ļ¼╝ņ¦ł(83.1%)ņŚÉ ļīĆĒĢśņŚ¼ 2 ng/L ņØ┤ĒĢśļĪ£ ņĀĢļ¤ēĒĢ£Ļ│ä (LOQ)ļŖö 145ņóģņØś ļ¼╝ņ¦ł (97.8%)ņŚÉ ļīĆĒĢśņŚ¼ 10 ng/L ņØ┤ĒĢśļĪ£ ļéśĒāĆļéś ļåÆņØĆ ļ»╝Ļ░ÉļÅäļź╝ ļ│┤ņŚ¼ņŻ╝ņŚłļŗż (Table 2). ņ”Øļźśņłśļź╝ ņØ┤ņÜ®ĒĢ£ ļīĆņāüļ¼╝ņ¦łņŚÉ ļīĆĒĢ£ ņĀłļīĆ ĒÜīņłśņ£© (Absolute Recovery)ņØś Ļ▓ĮņÜ░, ļ¬©ļæÉ 28~285% ņØ┤ļé┤ļĪ£ ļéśĒāĆļé¼Ļ│Ā, ņØ┤ļōż ņżæ 118ņóģ (79.7%)ņŚÉ ļīĆ ĒĢśņŚ¼ 75~125% ņØ┤ļé┤ļĪ£ ļéśĒāĆļéś ļåÆņØĆ ĒÜīņłśņ£©ņØä ļ│┤ņŚ¼ņŻ╝ņŚłļŗż.

ņĀĢļ¤ēļČäņäØ Ļ▓░Ļ│╝ ļīĆņāüļ¼╝ņ¦ł 148ņóģ ņżæ 71ņóģņØ┤ LOQ ņØ┤ņāüņØś ļåŹļÅäļĪ£ Ļ▓ĆņČ£ļÉśņŚłņ£╝ļ®░, ņØ┤ļōż ņżæ ļåŹņĢĮņØĆ 9ņóģ (12.7%), ņØś ņĢĮĒÆłņØĆ 41ņóģ (57.7%), ņé░ņŚģņÜ®ņĀ£ ļ░Å ĻĖ░ĒāĆļ¼╝ņ¦łņØĆ 21ņóģ (29.6%)ļĪ£ ļéśĒāĆļé¼ļŗż (Fig. 2).

ņŻ╝ņÜö ņśżņŚ╝ļ¼╝ņ¦łņØĆ ņ£ĀĻĖ░ņØĖĻ│äļé£ņŚ░ņĀ£ (Organophosphate flame retardant, OPFRs)ļĪ£ ņé¼ņÜ®ļÉśļŖö Tris(2-butoxyethyl) phosphate (TBEP)Ļ░Ć ņĄ£ļīĆ 14,000 ng/Lņ£╝ļĪ£ Ļ▓ĆņČ£ļÉśņŚłņ£╝ ļ®░, ņØ┤ ņÖĖņŚÉļÅä Metformin, Pentaethylene glycol, Cetirizine, galaxolidone, Acetaminophen, Heptaethylene glycol, Carbamazepine-10,11-epoxide, Sulfapyridine, Valsartan acid, Telmisartan, Fluconazole, Benzotriazole, Olmesartan, 4-Methyl-1H-benzotriazole, Sitagliptin, Perfluorohexanoic acid (PFHxA)Ļ░Ć ņĄ£ļīĆ 1,000 ng/L ņØ┤ņāüņ£╝ļĪ£ ļåÆĻ▓ī Ļ▓ĆņČ£ļÉśņŚłļŗż. ļ¼╝ņ¦łĻĘĖļŻ╣ļ│äļĪ£ ļéśļłäņ¢┤ ļ│┤ļ®┤, ņØśņĢĮĒÆł ņżæņŚÉņä£ļŖö ļŗ╣ļć©ļ│æ ņ╣śļŻīņĀ£ (Metformin, Sitagliptin), ĒĢŁĒ׳ņŖżĒāĆļ»╝ņĀ£ (Cetirizine), ĒĢŁņŚ╝ņ”ØņĀ£ (Acetaminophen), ĒĢŁĻ▓ĮļĀ©ņĀ£ ļīĆņé¼ņ▓┤ (Carbama-zepine-10,11-epoxide), Ļ│ĀĒśłņĢĢ ņ╣śļŻīņĀ£ ļīĆņé¼ņ▓┤ (Valsartan acid), ĒĢŁĻ░ÉņŚ╝ņĀ£ (Sulfapyridine), Ļ│ĀĒśłņĢĢ ņ╣śļŻīņĀ£ (Telmisartan, Olmesartan), ĒĢŁņ¦äĻĘĀņĀ£ (Fluconazole)Ļ░Ć 1,000 ng/L ņØ┤ņāü ļåÆņØĆ ļåŹļÅäļĪ£ ļéśĒāĆļé¼ļŗż. Acetaminophen (1,190~6,500 ng/L), Caffeine (320~65 ng/L), Naproxen (290~26 ng/L)ņØś Ļ▓ĮņÜ░, ņŗ£ļŻī ņ▒äņĘ©ĻĖ░Ļ░ä ļÅÖņĢł ņŗ£Ļ░äņŚÉ ļö░ļźĖ ļåŹļÅä ļ│ĆĒÖöĻ░Ć Ēü¼Ļ│Ā, ĒŖ╣Ē׳ ņśżņĀä 3~6ņŗ£Ļ▓Į Ļ░Ćņן ļåÆņØĆ Ļ▓āņ£╝ļĪ£ ļéśĒāĆļé¼ļŗż. ņØĖĻĘ╝ņŚÉ ņ£äņ╣śĒĢ£ ņä£ļČĆĒĢśņłśņ▓śļ”¼ņן ļ░Å ņä▒ņä£ĒÅÉņłśņ▓śļ”¼ņןņØĆ 24ņŗ£Ļ░ä ņ¦ĆņåŹ ļ░®ļźśĻ░Ć ņØ┤ļżäņ¦ĆĻ│Ā ņ׳ņ¢┤ ļ░®ļźśņŗ£Ļ░äņŚÉ ņØśĒĢ£ ņśüĒ¢źņØĆ ņ¢┤ļĀĄļŗżĻ│Ā ĒīÉļŗ©ļÉ£ļŗż. ĒĢ┤ļŗ╣ ļ¼╝ņ¦łņØś Ļ▓ĮņÜ░, ņØ╝ļ░śņĀüņ£╝ļĪ£ ņØĖĻ░äņØś ņŻ╝Ļ░ä ņāØĒÖ£ņŗ£Ļ░äņØĖ ņśżņĀä 7ņŗ£~ņśżĒøä 6ņŗ£ņŚÉ ņé¼ņÜ®ļ¤ēņØ┤ ļ¦Äņ£╝ļ®░, ĒĢśĒÅÉņłśņ▓śļ”¼ņןņŚÉ ņ£Āņ×ģļÉ£ Ēøä ņłśņ▓śļ”¼ Ļ│╝ņĀĢ (18~19ņŗ£Ļ░ä)ņØä Ļ▒░ņ│É ņ¦ĆĒæ£ņłśļĪ£ ļ░®ļźśļÉ£ļŗż. ĒĢ┤ļŗ╣ ļ¼╝ņ¦ł ņé¼ņÜ®ļ¤ēņØ┤ ļ¦ÄņØĆ ĒŖ╣ņĀĢ ņŗ£Ļ░äļīĆ ļśÉĒĢ£ ļåŹļÅä ļ│ĆĒÖöņØś ņøÉņØĖ ņżæ ĒĢśļéśļĪ£ ĒīÉļŗ©ļÉ£ļŗż. Valsartan acidļŖö valsartan, losartan, irbesartanņØś ņŻ╝ņÜö ļīĆņé¼ļ¼╝ņ¦łļĪ£, ĒĢśņłśņ▓śļ”¼Ļ│╝ņĀĢņØ┤ ņŻ╝ņÜö ņāØņä▒ ņøÉņØĖņ£╝ļĪ£ ņĢīļĀżņĀĖ ņ׳ļŗż[17,18]. Ļ▓ĆņČ£ļÉ£ ļ¼╝ņ¦ł ĻĘĖļŻ╣ ņżæ Ļ│ĀĒśłņĢĢ ņ╣śļŻīņĀ£ļŖö ņ┤Ø 42ņóģņØś ņØśņĢĮļ¼╝ņ¦ł ņżæ 8ņóģ (19%)ļź╝ ņ░©ņ¦ĆĒĢśĻ│Ā ņ׳ņ£╝ļ®░, Ļ│ĀĒśłņĢĢ ņ╣śļŻīņĀ£ļĪ£ ņŻ╝ļĪ£ ņō░ņØ┤ļŖö sartan Ļ│äņŚ┤ņØś ļ¼╝ņ¦łļōżņØĆ ĻŠĖņżĆĒ׳ ņ¦ĆĒæ£ņłśņŚÉņä£ ļåÆņØĆ ļåŹļÅäļĪ£ ņ×ÉņŻ╝ ļ│┤Ļ│ĀļÉśĻ│Ā ņ׳ļŗż. ĒŖ╣Ē׳, TelmisartanņØś Ļ▓ĮņÜ░, ņĄ£ĻĘ╝ ļ¬ć ļģä Ļ░ä ļéÖļÅÖĻ░Ģ ņłśĻ│äņŚÉņä£ ļåÆņØĆ ļåŹļÅäļĪ£ Ļ▓ĆņČ£ļÉśĻ│Ā ņ׳ņ£╝ļ®░[19,20, ņäĀĒ¢ē ņŚ░ĻĄ¼ņŚÉņä£ ņ¦ĆĒæ£ņłś ļé┤ ņÜ░ņäĀņł£ņ£äļ¼╝ņ¦ł ņäĀņĀĢņŚÉņä£ ļåÆņØĆ ņł£ņ£äļĪ£ ņäĀņĀĢļÉ£ ļ░ö ņ׳ņ¢┤ ņłśņāØĒā£Ļ│ä ļé┤ ņĢģņśüĒ¢źņØä ļ»Ėņ╣Ā Ļ▓āņ£╝ļĪ£ ĒīÉļŗ©ļÉ£ļŗż. ņØ┤ ņÖĖņŚÉļÅä Ļ│ĀĒśłņĢĢ ņ╣śļŻīņĀ£ (Atenolol), ĻĄ¼ņČ®ņĀ£ ļīĆņé¼ņ▓┤ (Albendazole sulfoxide), ĒĢŁļČĆņĀĢļ¦źņĀ£ (Lidocaine) ļŗ╣ļć©ļ│æ ņ╣śļŻīņĀ£ (Valsartan) ļō▒ņØ┤ ņŻ╝ņÜö ļ¼╝ņ¦łļĪ£ņŹ© ĒÖĢņØĖļÉśņŚłļŗż. ļŗżļźĖ ļ¼╝ņ¦ł ĻĘĖļŻ╣ (ļåŹņĢĮ, ņé░ņŚģņÜ®ņĀ£ ļ░Å ĻĖ░ĒāĆ) ņŚÉ ļ╣äĒĢ┤ ņāüļīĆņĀüņ£╝ļĪ£ ļ¦ÄņØĆ ņóģļźśņØś ļ¼╝ņ¦łņØ┤ Ļ▓ĆņČ£ļÉśņŚłņ£╝ļ®░, ņØ┤ļŖö ņŗ£ļŻī ņ▒äņĘ© ņ¦ĆņĀÉ ņØĖĻĘ╝ņŚÉ ņ£äņ╣śĒĢ£ ĒĢśĒÅÉņłśņ▓śļ”¼ņןņØ┤ ĻĘĖ ņøÉņØĖņ£╝ļĪ£ ņé¼ļŻīļÉ£ļŗż.

ņé░ņŚģņÜ®ņĀ£ ļ░Å ĻĖ░ĒāĆļ¼╝ņ¦łņØś Ļ▓ĮņÜ░, ņ£ĀĻĖ░ņØĖĻ│äļé£ņŚ░ņĀ£ (Tris(2-butoxyethyl) phosphate (TBEP), Tris(2-chloroethyl) pho-sphate (TCEP)ļź╝ ļ╣äļĪ»ĒĢ£ ĒĢ®ņä▒ĒĢŁļŻī ļīĆņé¼ņ▓┤ (Galaxolidone), ļČĆņŗØļ░®ņ¦ĆņĀ£ ļīĆņé¼ņ▓┤ (4-Methyl-1H-benzotriazole), Ļ│äļ®┤ĒÖ£ņä▒ņĀ£ (Heptaethylene glycol, Pentaethylene glycol), ļČĆņŗØļ░®ņ¦ĆņĀ£ (Benzotriazole), Ļ│╝ļČłĒÖöĒÖöĒĢ®ļ¼╝ (Per-and poly-fluoroalkyl substances, PFAS) PFHxAĻ░Ć ļåÆņØĆ ļåŹļÅäļĪ£ Ļ▓ĆņČ£ļÉśņŚłļŗż. ņ£ĀĻĖ░ņØĖĻ│ä ļé£ņŚ░ņĀ£ļŖö ņāØļ¼╝ļåŹņČĢņä▒ ļ░Å ļé£ļČäĒĢ┤ņä▒ ĒŖ╣ņä▒ņ£╝ļĪ£ ņØĖĒĢ┤ ņé¼ņÜ®ņØ┤ ĻĖłņ¦ĆļÉ£ ļĖīļĪ¼Ļ│äļé£ņŚ░ņĀ£ (e.g, PBDES)ņØś ļīĆņ▓┤ņĀ£ļĪ£ ņé¼ņÜ®ļ¤ēņØ┤ ĻĖēĻ▓®Ē׳ ņ”ØĻ░ĆĒĢśļ®┤ņä£ ņ¦ĆĒæ£ņłśņŚÉņä£ ļåÆņØĆ ļåŹļÅäļĪ£ Ļ▓ĆņČ£ļÉśĻ│Ā ņ׳ļŗż[21,22,23]. BenzotriazoleņØĆ ņ╣£ņłśņä▒ņØ┤ Ļ░ĢĒĢ┤ ĒĢśĒÅÉņłśņ▓śļ”¼ņןņŚÉņä£ņØś ņĀ£Ļ▒░ĒÜ©ņ£©ņØ┤ ļé«ņĢä ņ¦ĆĒæ£ņłś ļé┤ ļ╣äĻĄÉņĀü ļåÆņØĆ ļåŹļÅäļĪ£ ļČäĒżĒĢ£ļŗż[24]. Ļ│╝ļČłĒÖöĒÖöĒĢ®ļ¼╝ņØĆ ņ┤Ø 10ņóģņØ┤ ĒÖĢņØĖļÉśņŚłĻ│Ā ĻĘĖ ņżæ PFHxA ļ░Å Perfluoropentanoic acid (PFPeA)Ļ░Ć ņŻ╝ņÜö ļ¼╝ņ¦łļĪ£ ĒÖĢņØĖļÉśņŚłļŗż. ņØ┤ļź╝ ņĀ£ņÖĖĒĢ£ Ļ│╝ļČłĒÖöĒÖöĒĢ®ļ¼╝ļōżņØĆ ļŗżļźĖ ņé░ņŚģņÜ®ņĀ£ņŚÉ ļ╣äĒĢ┤ ņāüļīĆņĀüņ£╝ļĪ£ ļé«ņØĆ ļåŹļÅäļĪ£ ļéśĒāĆļé¼ņ¦Ćļ¦ī, ļéÖļÅÖĻ░Ģ ņłśĻ│äņŚÉņä£ ļŗżņ¢æĒĢ£ ĒśĢĒā£ņØś Ļ│╝ļČłĒÖöĒÖöĒĢ®ļ¼╝ņØ┤ ņĪ┤ņ×¼ĒĢśĻ│Ā ņ׳ļŖö Ļ▓āņ£╝ļĪ£ ĒīÉļŗ©ļÉ£ļŗż. ļåŹņĢĮņØĆ ņé┤ņČ®ņĀ£ ļīĆņé¼ņ▓┤ (2-hydroxybenzimidazole), ņé┤ĻĘĀņĀ£ (penconazole)Ļ░Ć 100 ng/L ņØ┤ņāüņ£╝ļĪ£ ļéśĒāĆļé¼Ļ│Ā, ļŗżļźĖ ļ¼╝ņ¦ł ĻĘĖļŻ╣ņŚÉ ļ╣äĒĢ┤ ņāüļīĆņĀüņ£╝ļĪ£ ļé«ņØĆ ļåŹļÅäļĪ£ Ļ▓ĆņČ£ļÉśņŚłļŗż. ņŗ£ļŻī ņ▒äņĘ© ņØ╝ņ×ÉņØĖ 5ņøöņØś Ļ▓ĮņÜ░, ĒĢ£ņ░Į ļåŹņĢĮ ņé¼ņÜ®ņØ┤ ņ”ØĻ░ĆĒĢśļŖö ņŗ£ņĀÉņØ┤ņ¦Ćļ¦ī Ļ▓ĆņČ£ļÉ£ ļåŹņĢĮņØś ņóģļźś ļ░Å ļåŹļÅäĻ░Ć ļé«ņØĆ Ļ▓āņØĆ ņŗ£ļŻī ņ▒äņĘ© ņ¦ĆņĀÉ ņ£äņ╣śņāü Ļ│Ąļŗ© ļ░Å ĒĢśĒÅÉņłśņ▓śļ”¼ņן ĻĘ╝ņ▓śņŚÉ ņ׳ņ¢┤ ļåŹņĢĮņØś ņŻ╝ņÜö ņ£Āņ×ģ ņøÉņØĖņØĖ ļåŹĻ▓Įņ¦Ć ļ░Å ĒåĀņ¢æ ņ£ĀņČ£ņŚÉļŖö ļ╣äĻĄÉņĀü ņśüĒ¢źņØä ļŹ£ ļ░øĻĖ░ ļĢīļ¼ĖņØ┤ļØ╝ ĒīÉļŗ©ļÉ£ļŗż. Ļ▓Įņ×æņŗ£ĻĖ░ņŚÉ ļö░ļØ╝ ļ¼╝ņ¦ł ļ░Å ņé¼ņÜ®ļ¤ēņØ┤ ļŗ¼ļØ╝ņ¦ĆĻ▓Āņ¦Ćļ¦ī, ņØĖĻĘ╝ņŚÉ ņ£äņ╣śĒĢ£ ļīĆĻĘ£ ņāüļźśņØś ļåŹĻ▓Įņ¦ĆņŚŁņŚÉ ņśüĒ¢źņØä ļ░øļŖö Ļ░Ģņ░ĮĻĄÉņÖĆ ļ╣äĻĄÉĒ¢łņØä ļĢī, 27ņóģņØ┤ Ļ▓ĆņČ£ļÉ£ Ļ░Ģņ░ĮĻĄÉņÖĆ ļŗ¼ļ”¼ ļŗ© 9ņóģļ¦īņØ┤ Ļ▓ĆņČ£ļÉśņŚłļŗż. ļśÉĒĢ£ Ļ▓ĆņČ£ļÉ£ ļåŹņĢĮņØś ļåŹļÅäĒĢ®ņØ┤ 1,000 ng/L ņØ┤ņāüņØĖ Ļ░Ģņ░ĮĻĄÉņÖĆ ļ╣äĻĄÉĒĢśņŚ¼ 360 ng/Lņ£╝ļĪ£ ņĢĮ 3ļ░░ņĀĢļÅä ņ░©ņØ┤Ļ░Ć ļé¼ļŗż16.

Ļ▓ĆņČ£ļÉ£ 71ņóģņØś ļ¼╝ņ¦łļōżņØś ņŗ£ļŻī ņ▒äņĘ© ĻĖ░Ļ░ä ļÅÖņĢłņØś ļåŹļÅäļŖö ļŗżņ¢æĒĢ£ ĒśĢĒā£ļĪ£ ļéśĒāĆļé¼ņ£╝ļ®░, ņŗ£Ļ░äņØ┤ Ļ▓ĮĻ│╝ĒĢ©ņŚÉ ļö░ļØ╝ ļåŹļÅäĻ░Ć ņØ╝ņĀĢĒĢ£ ļ¼╝ņ¦ł, ņä£ņä£Ē׳ ļåŹļÅäĻ░Ć Ļ░Éņåī ļśÉļŖö ņ”ØĻ░ĆĒĢśļŖö ļ¼╝ņ¦ł, ņŗ£Ļ░äĻ│╝ Ļ┤ĆĻ│äņŚåņØ┤ ļåŹļÅäĻ░Ć ĻĖēĻ▓®Ē׳ ļ│ĆĒĢśļŖö ļ¼╝ņ¦ł ļō▒ņØ┤ ĒżĒĢ©ļÉśņ¢┤ ņ׳ļŗż. ĻĘĖ ņżæ ĒŖ╣ņØ┤ņĀüņ£╝ļĪ£ Ļ│╝ļČłĒÖöĒÖöĒĢ®ļ¼╝Ļ│╝ benzotriazole Ļ│äņŚ┤ņØś ļ¼╝ņ¦łļōżņØ┤ Ļ░üĻ░ü ņŗ£Ļ░äņŚÉ ļö░ļźĖ ļ╣äņŖĘĒĢ£ ļåŹļÅä ļ│ĆĒÖö Ļ▓ĮĒ¢źņä▒ņØ┤ ļéśĒāĆļé¼ļŗż (Fig. 3). Ļ│╝ļČłĒÖöĒÖöĒĢ®ļ¼╝ņØĆ ņØĖņ£äņĀüņ£╝ļĪ£ ļ¦īļōżņ¢┤ņ¦ä ņ£ĀĻĖ░ĒÖöĒĢ®ļ¼╝ ņżæ ĒĢ£ ņóģļźśļĪ£[25,26], Ļ░ĢļĀźĒĢ£ C-F ĒÖöĒĢÖĻ▓░ĒĢ®ņ£╝ļĪ£ ļåÆņØĆ ņ×öļźśņä▒ņØä ņ¦Ćļģöņ£╝ļ®░, ņŚ┤ņĀüņ£╝ļĪ£ ņĢłņĀĢĒĢśĻ│Ā, ļ░®ņłś, ļ░®ņśż, ļ░£ņ£Ā ĒŖ╣ņä▒ņ£╝ļĪ£ ņØĖĒĢśņŚ¼ 1950ļģäļīĆļČĆĒä░ Ļ┤æļ▓öņ£äĒĢśĻ▓ī ņé¼ņÜ®ļÉśņ¢┤ ņÖöļŗż[27,28]. ĻĘĖļ¤¼ļéś PFAS ļ¼╝ņ¦łņØĆ ņēĮĻ▓ī ļČäĒĢ┤ļÉśņ¦Ć ņĢŖĻĖ░ ļĢīļ¼ĖņŚÉ ĒÖśĻ▓Į ļ░Å ņØĖņ▓┤ ļé┤ņŚÉņä£ Ļ┤æļ▓öņ£äĒĢśĻ▓ī ļ░£Ļ▓¼ļÉśĻ│Ā ņ׳ņ£╝ļ®░, ļ░£ņĢöņä▒, ņāØļåŹņČĢņä▒, ņāØņŗØļÅģņä▒ņØä ņ¦Ćļŗī ņ×öļźśņä▒ ļÅģņä▒ ļ¼╝ņ¦łļĪ£ ņĢīļĀżņĀĖ ņ׳ļŗż. ņØ┤ļ¤░ ĒŖ╣ņä▒ņ£╝ļĪ£ ņØĖĒĢ┤ ĻĄŁņĀ£ņĀüņ£╝ļĪ£ PFASļ¼╝ņ¦łņØś ņé¼ņÜ® ļ░Å ņ£ĀĒåĄņØ┤ ĻĘ£ņĀ£ļÉśĻ│Ā ņ׳ļŗż. Ļ▓ĆņČ£ļÉ£ Ļ│╝ļČłĒÖöĒÖöĒĢ®ļ¼╝ņØĆ ņ”ØĻ░ĆĒĢśļŗżĻ░Ć Ļ░ÉņåīĒĢśļŖö ĒśĢĒā£ļĪ£, 5ņøö 9ņØ╝ 12ņŗ£ 30ļČäņØä ĻĖ░ņĀÉņ£╝ļĪ£ ņä£ņä£Ē׳ ļåŹļÅäĻ░Ć ņ”ØĻ░ĆĒĢśļŗżĻ░Ć 5ņøö 10ņØ╝ 00ņŗ£ 30ļČäņØĖ ņāłļ▓Į ņŗ£Ļ░äļīĆņŚÉ Ļ░Ćņן ļåÆĻ▓ī ļéśĒāĆļé£ Ēøä Ļ░ÉņåīĒĢ£ļŗż. Ļ│ĀļåŹļÅäļĪ£ Ļ▓ĆņČ£ļÉ£ PFHxAņØś Ļ▓ĮņÜ░, 370~1,200 ng/LņØś ļåŹļÅä ļ▓öņ£äļź╝ ļéśĒāĆļé¼ņ£╝ļ®░, ņØ┤ĒŗĆņØ┤ļØ╝ļŖö ņŗ£Ļ░äņŚÉņä£ ņĢĮ 3ļ░░ ņĀĢļÅäņØś ļåŹļÅä ļ│ĆĒÖöĻ░Ć ļéśĒāĆļé¼Ļ│Ā, ņ£ĀņØśļ»ĖĒĢśļŗżĻ│Ā ĒīÉļŗ©ļÉ£ļŗż. PFHxAņØś Ļ│ĀļåŹļÅä Ļ▓ĆņČ£ņØĆ C8~C14 ņé¼ņŖ¼ņØĖ PFOA, PFCAS ņØś ņé¼ņÜ®ņØ┤ ņĀ£ĒĢ£ļÉ©ņŚÉ ļö░ļØ╝, C6ņØĖ ļ╣äĻĄÉņĀü ņ¦¦ņØĆ ņé¼ņŖ¼ņØĖ PFHxAņØä ņé¼ņÜ®ĒĢśĻĖ░ ņŗ£ņ×æĒĢ©ņ£╝ļĪ£ņŹ© ļéśĒāĆļé£ ĒśäņāüņØ┤ļØ╝ ņśłņāüļÉ£ļŗż. ĻĄŁļé┤ņØś Ļ▓ĮņÜ░, PFASņŚÉ ļīĆĒĢ£ ņĀäņłśņĪ░ņé¼ņÖĆ ņé¼ņÜ®ĻĖłņ¦Ć, ĻĘ£ņĀ£ ļ¦łļĀ© ņ┤ēĻĄ¼ ļō▒ņØś ņøĆņ¦üņ×äņØĆ Ļ│äņåŹ ņ׳ņ¢┤ņÖöņ¦Ćļ¦ī, Ēśäņ×¼ ļ░®ļźśņłśņŚÉ ļīĆĒĢ£ ļ░░ņČ£ ĻĖ░ņżĆ ļ░Å Ļ┤Ćļ”¼ĻĖ░ņżĆņØ┤ ņŚåĻĖ░ņŚÉ ĻĖ░ņżĆņØ┤ ĒĢäņÜöĒĢ£ ņāüĒÖ®ņØ┤ļŗż. BenzortriazoleņØĆ ņØ╝ļ░śņĀüņ£╝ļĪ£ ņé░ņŚģ Ļ│ĄņĀĢņŚÉņä£ ļČĆņŗØļ░®ņ¦ĆņĀ£ ļ░Å ņäĖņĀĢņĀ£ļĪ£ ņé¼ņÜ®ļÉśļ®░, ĒÖśĻ▓Į ņżæ ņ£Āņ×ģ ņŗ£ ļŗżņ¢æĒĢ£ ĒśĢĒā£ņØś ļ│ĆĒÖśņ▓┤ļź╝ ņāØņä▒ĒĢ£ļŗż. ĒĢ┤ļŗ╣ Ļ│äņŚ┤ņØś ļ¼╝ņ¦ł ļōż ļśÉĒĢ£ ļ╣äņŖĘĒĢ£ ņ¢æņāüņØś ļåŹļÅä ļ│ĆĒÖöļź╝ ļéśĒāĆļāłļŖöļŹ░, ņä£ņä£Ē׳ ņ”ØĻ░ĆĒĢśļŗżĻ░Ć ņāłļ▓Įņŗ£Ļ░äļīĆņØĖ 5/10 02ņŗ£ļź╝ ĻĖ░ņĀÉņ£╝ļĪ£ Ļ░Ćņן ļåÆņØĆ ļåŹļÅäļĪ£ Ļ▓ĆņČ£ļÉ£ Ēøä ņä£ņä£Ē׳ Ļ░ÉņåīĒĢśļŖö Ļ▓āņØä ļ│╝ ņłś ņ׳ļŗż. ņØ┤ļŖö ņĢ×ņä£ ļ¦ÉĒĢ£ Ļ│╝ļČłĒÖöĒÖöĒĢ®ļ¼╝ņØś ņŗ£Ļ░äņŚÉ ļö░ļźĖ ļåŹļÅäļ│ĆĒÖö ĻĘĖļלĒöäņÖĆ ļ╣äņŖĘĒĢ£ ņ¢æņāüņØä ļ│┤ņØ┤Ļ│Ā ņ׳ņ£╝ļ®░, ņŗ£ļŻīņ▒äņĘ© ņ¦ĆņĀÉ ņØĖĻĘ╝ņŚÉ ņ£äņ╣śĒĢ£ ļīĆĻĘ£ļ¬© Ļ│Ąļŗ©ņŚÉņä£ ļ░£ņāØļÉśļŖö ĒÅÉņłśņØś ņśüĒ¢źņ£╝ļĪ£ ĒīÉļŗ©ļÉ£ļŗż. Ļ│╝ļČłĒÖöĒÖöĒĢ®ļ¼╝ ļ░Å benzotriazoleņØĆ ņé░ņŚģĻ│ĄņĀĢņŚÉņä£ ņŻ╝ļĪ£ ņé¼ņÜ®ļÉśļŖö ļ¼╝ņ¦łļĪ£ņŹ© ņØĖĻĘ╝ Ļ│Ąļŗ©ņŚÉņä£ņØś ņŻ╝ ņé¼ņÜ®ņŗ£Ļ░ä ļśÉĒĢ£ ņÜöņØĖ ņżæ ĒĢśļéśļØ╝ ļ│┤ņŚ¼ņ¦äļŗż. ņČöĒøä ņןĻĖ░Ļ░ä ņŗ£ļŻīņ▒äņĘ©ļź╝ ĒåĄĒĢ£ ļæÉ ļ¼╝ņ¦łņŚÉ ņŗ£Ļ░äņŚÉ ļö░ļźĖ ļåŹļÅäļ│ĆĒÖöņØś ņāüĻ┤ĆĻ┤ĆĻ│äļź╝ ĒīīņĢģĒĢĀ ĒĢäņÜöĻ░Ć ņ׳ļŗż.

ļ│Ė ņŚ░ĻĄ¼ņŚÉņä£ļŖö ņ¦ĆĒæ£ņłś ļé┤ ņĪ┤ņ×¼ĒĢśļŖö ļ»Ėļ¤ēņśżņŚ╝ļ¼╝ņ¦łņØś ļČäĒż ļ░Å ņØ╝ļČĆ ļ¼╝ņ¦ł ĻĘĖļŻ╣ņØś ņŗ£Ļ░äņŚÉ ļö░ļźĖ ļåŹļÅä ļ│ĆĒÖöļź╝ ĒīīņĢģĒĢśĻĖ░ ņ£äĒĢ┤ 148ņóģņØś ļ¼╝ņ¦łņŚÉ ļīĆĒĢ£ LC-HRMS ĻĖ░ļ░ś ņĀĢļ¤ēļČäņäØņØä ņłśĒ¢ēĒĢśņśĆļŗż. ĻĘĖ Ļ▓░Ļ│╝ ņ┤Ø 71ņóģņØś ļ¼╝ņ¦łņØ┤ LOQ ņØ┤ņāüņØś ļåŹļÅäļĪ£ Ļ▓ĆņČ£ļÉśņŚłĻ│Ā, ĒĢśĒÅÉņłśņ▓śļ”¼ņן ņØĖĻĘ╝ņŚÉ ņ£äņ╣śĒĢ£ ņŗ£ļŻī ņ▒äņĘ©ņ¦ĆņĀÉ ĒŖ╣ņä▒ ņāü ļŗżļźĖ ļ¼╝ņ¦ł ĻĘĖļŻ╣ņŚÉ ļ╣äĒĢ┤ ņØśņĢĮĒÆłņØ┤ Ļ░Ćņן ļ¦ÄņØĆ ļ¼╝ņ¦łņØä ĒżĒĢ©ĒĢśņśĆļŗż. ņŻ╝ņÜö ņśżņŚ╝ļ¼╝ņ¦łļĪ£ļŖö ņ£ĀĻĖ░ņØĖĻ│äļé£ņŚ░ņĀ£ļĪ£ ņé¼ņÜ®ļÉśļŖö TBEPĻ░Ć ņĄ£ļīĆ 14,000 ng/Lņ£╝ļĪ£ Ļ▓ĆņČ£ļÉśņŚłņ£╝ļ®░, ņØ┤ ņÖĖņŚÉļÅä Metformin, Pentaethylene glycol, Cetirizine, galaxolidone, Acetaminophen, Heptaethylene glycol, Carbamazepine-10,11-epoxide, Sulfapyridine, Valsartan acid, Telmisartan, Fluconazole, Benzotriazole, Olmesartan, 4-Methyl-1H-benzotriazole, Sitagliptin, PFHxAĻ░Ć ņĄ£ļīĆ 1,000 ng/L ņØ┤ņāüņ£╝ļĪ£ ļåÆĻ▓ī Ļ▓ĆņČ£ļÉśņŚłļŗż. Ļ▓ĆņČ£ļÉ£ ļ¼╝ņ¦łļōżņØ┤ ņŗ£Ļ░ä Ļ▓ĮĻ│╝ņŚÉ ļö░ļźĖ ļåŹļÅä ļ│ĆĒÖöļŖö ļŗżņ¢æĒĢ£ ņ¢æņāüņ£╝ļĪ£ ļéśĒāĆļé¼ņ£╝ļ®░, ĒŖ╣Ē׳ ļīĆņāüļ¼╝ņ¦ł ņżæ Ļ│╝ļČłĒÖöĒÖöĒĢ®ļ¼╝Ļ│╝ benzotriazole Ļ│äņŚ┤ņØś ļ¼╝ņ¦łļōżņØ┤ Ļ░üĻ░ü ņŗ£Ļ░äņŚÉ ļö░ļźĖ ļ╣äņŖĘĒĢ£ ļåŹļÅä ļ│ĆĒÖöļź╝ ļéśĒāĆļāłļŗż. ļśÉĒĢ£ ļæÉ ļ¼╝ņ¦ł ĻĘĖļŻ╣ ļ¬©ļæÉ ņāłļ▓Įņŗ£Ļ░äļīĆņØĖ 5/10 00ņŗ£ 30ļČä~02ņŗ£ņŚÉņä£ Ļ░Ćņן ļåÆņØĆ ļåŹļÅäļź╝ ļéśĒāĆļāłņ£╝ļ®░, ĻĘĖ Ēøä ņä£ņä£Ē׳ Ļ░ÉņåīĒĢśļŖö ņ¢æņāüņØä ļ│┤ņŚ¼ņż¼ļŗż. ņØ┤ļ¤¼ĒĢ£ ļåŹļÅä ļ│ĆĒÖöņØś ņŻ╝ ņÜöņØĖņ£╝ļĪ£ļŖö ņŗ£ļŻīņ▒äņĘ©ņ¦ĆņĀÉ ņØĖĻĘ╝ņŚÉ ņ£äņ╣śĒĢ£ ĒĢśĒÅÉņłśņ▓śļ”¼ņןņØś ļ░®ļźśņłśļĪ£ ļ│┤ņŚ¼ņ¦Ćļ®░, ņØĖĻĘ╝ņØś ļīĆĻĘ£ļ¬© Ļ│Ąļŗ©ņŚÉņä£ ĒĢ┤ļŗ╣ ļ¼╝ņ¦łņØä ņé¼ņÜ®ĒĢśļŖö ņŗ£Ļ░äļīĆ ļśÉĒĢ£ ņÜöņØĖ ņżæ ĒĢśļéśļĪ£ ļ│┤ņŚ¼ņ¦äļŗż. ņĢĮ ņØ┤ĒŗĆ Ļ░äņØś ņ¦¦ņØĆ ņ▒äņĘ©ĻĖ░Ļ░äņ×äņŚÉļÅä ļČłĻĄ¼ĒĢśĻ│Ā, ņØ╝ļČĆ ļ¼╝ņ¦łņØś Ļ▓ĮņÜ░ ļåŹļÅä ļ│ĆĒÖö ĒÅŁņØ┤ ņ╗Ėņ£╝ļ®░, ņŗ£Ļ░äņŚÉ ļö░ļźĖ ņłśņāØĒā£Ļ│äņŚÉ ļ»Ėņ╣śļŖö ņ£äĒĢ┤ņä▒ ļśÉĒĢ£ ļ│ĆĒÖöĒĢĀ Ļ▓āņØ┤ļØ╝ ņé¼ļŻīļÉ£ļŗż. ņČöĒøä, ņ▒äņĘ© ĻĖ░Ļ░äņØä ļŖśļĀż ņ¦ĆĒæ£ņłś ļé┤ ļ»Ėļ¤ēņśżņŚ╝ļ¼╝ņ¦ł ļåŹļÅäņØś Ļ▓ĮĒ¢źņä▒ņØä ĒīīņĢģĒĢśĻ│Ā, ļåŹļÅä ļ│ĆĒÖöļĪ£ ņØĖĒĢ£ ņłśņāØĒā£Ļ│ä ļé┤ ņ£äĒĢ┤ņä▒ ļ│ĆĒÖöļź╝ ĒÖĢņØĖĒĢĀ ĒĢäņÜöĻ░Ć ņ׳ļŗż.

Ļ░Éņé¼ņØś ĻĖĆ

ņØ┤ ņŚ░ĻĄ¼ļŖö 2022ļģäļÅä ņ░ĮņøÉļīĆĒĢÖĻĄÉ ļīĆĒĢÖņøÉ ņĀäņØ╝ņĀ£ ņŚ░ĻĄ¼ ņןĒĢÖņāØ ņ¦ĆņøÉņé¼ņŚģņ£╝ļĪ£ ņłśĒ¢ēļÉśņŚłņŖĄļŗłļŗż.

Fig.┬Ā1.

Location for the sampling site (STP: Sewage Treatment Plant, WWTP: Waste-Water Treatment Plant).

Table┬Ā1.

Information on reference standards and internal reference standards used in the analysis

Table┬Ā2.

Information on the limit of detection (LOD), limit of quantification (LOQ), and absolute recovery (Rec) of the 148 target substances

ņ░ĖĻ│Āļ¼ĖĒŚī

1. A. Gosset, L. Wiest, A. Fildier, C. Libert, B. Giroud, M. Hammada, M. Herv├®, E. Sibeud, E. Vulliet, P. Polom├®, and Y. Perrodin, ŌĆ£Ecotoxicological risk assessment of contaminants of emerging concern identified by ŌĆśSuspect screeningŌĆÖ from urban wastewater treatment plant effluents at a territorial scaleŌĆØ, Science of The Total Environment, 2021, 778, 146275.

2. J. Wang, and L. Chu, ŌĆ£Irradiation treatment of pharmaceutical and personal care products (PPCPs) in water and wastewater: An overviewŌĆØ, Radiation Physics and Chemistry, 2016, 125, 56-64.

3. W. Sim, J. Lee, and J. Oh, ŌĆ£Occurrence and fate of pharmaceuticals in wastewater treatment plants and rivers in KoreaŌĆØ, Environmental pollution, 2010, 158 (5), 1938-1947.

4. G. McEneff, L. Barron, B. Kelleher, B. Paull, and B. Quinn, ŌĆ£A year-long study of the spatial occurrence and relative distribution of pharmaceutical residues in sewage effluent, receiving marine waters and marine bivalvesŌĆØ, Science of The Total Environmental, 2014, 476-477. , 317-326

5. R. Guillossou, J. L. Roux, R. Mailler, E. Vulliet, C. Morlay, F. Nauleau, J. Gasperi, and V. Rocher, ŌĆ£Organic micropollutants in a large wastewater treatment plant: What are the benefits of an advanced treatment by activated carbon adsorption in comparison to conventional treatment?ŌĆØ Chemosphere, 2019, 218, 1050-1060.

6. Z. Tou┼Īov├Ī, B. Vrana, M. Smutna, J. Novak, V. Klucarova, R. Grabic, J. Slobodnik, J. P. Giesy, and K. Hilscherova, ŌĆ£Analytical and bioanalytical assessments of organic micropollutants in the Bosna River using a combination of passive sampling, bioassays and multi-residue analysisŌĆØ, Science of the total environment, 2019, 650, 1599-1612.

7. C. M. G. Carpenter, L. Y. J. Wong, C. A. Johnson, and D. E. Helbling, ŌĆ£Fall creek monitoring station: highly resolved temporal sampling to prioritize the identification of nontarget micropollutants in a small streamŌĆØ, Environmental science and technology, 2019, 53, 77-87.

8. C. M. G. Carpenter, L. Y. J. Wong, D. L. Gutema, and D. E. Helbling, ŌĆ£Fall creek monitoring station: using environmental covariates to predict micropollutant dynamics and peak events in surface water systemsŌĆØ, Environmental science and technology, 2019, 53, 8599-8610.

9. L. L. Hohrenk, M. Vosough, and T. C. Schmidt, ŌĆ£Implementation of Chemometric Tools to Improve Data Mining and Prioritization in LC-HRMS for Nontarget Screening of Organic Micropollutants in Complex Water MatrixesŌĆØ, Analytical Chemistry, 2019, 91, 9213-9220.

10. L. Maurer, C. Villette, J. Zumsteg, A. Wanko, and D. Heintz, ŌĆ£Large scale micropollutants and lipids screening in the sludge layers and the ecosystem of a vertical flow constructed wetlandŌĆØ, Science of the Total Environment, 2020, 746, 141196.

11. N. A. Alygizakis, S. Samanipour, J. Hollender, M. Ib├Ī├▒ez, S. Kaserzon, V. Kokkali, J. A. van Leerdam, J. F. Mueller, M. Pijnappels, M. J. Reid, E. L. Schymanski, J. Slobodnik, N. S. Thomaidis, and K. V. Thomas, ŌĆ£Exploring the Potential of a Global Emerging Contaminant Early Warning Network through the Use of Retrospective Suspect Screening with High-Resolution Mass SpectrometryŌĆØ, Environmental science and technology, 2018, 52, 5135-5144.

12. W. Brack, J. Hollender, M. L. de Alda, C. M├╝ller, T. Schulze, E. Schymanski, J. Slobodink, and M. Krauss, ŌĆ£High-resolution mass spectrometry to complement monitoring and track emerging chemicals and pollution trends in European water resourcesŌĆØ, Environmental Science Europe, 2019, 31, 62.

13. E. L. Schymanski, H. P. Singer, P. Longr├®e, M. Loos, M. Ruff, M. A. Stravs, C. R. Vidal, and J. Hollender, ŌĆ£Strategies to characterize polar organic contamination in wastewater: Exploring the capability of High Resolution Mass SpectrometryŌĆØ, Environmental science and technology, 2014, 48, 1811-1818.

14. L. Lian, S. Yan, H. Zhou, and W. Song, ŌĆ£Overview of the Phototransformation of Wastewater Effluents by High-Resolution Mass SpectrometryŌĆØ, Environmental science and technology, 2020, 54, 1816-1826.

15. M. Oss, A. Kruve, K. Herodes, and I. Leito, ŌĆ£Electrospray ionization efficiency scale of organic compoundsŌĆØ, Analytical Chemistry, 2010, 82 (7), 2865-2872.

16. N. Park, D. Kang, and J. Jeon, ŌĆ£Occurrence and Concentration of Micropollutants in the Middle-and Down-stream of Nakdong RiverŌĆØ, Journal of Environmental Analysis, Health and Toxicology, 2021, 24 (1), 1-12.

17. T. Letzel, A. Bayer, W. Schulz, A. Heermann, T. Lucke, G. Greco, S. Grosse, W. Sch├╝ssler, M. Sengl, and M. Letzel, ŌĆ£LC-MS screening techniques for wastewater analysis and analytical data handling strategies: Sartans and their transformation products as an exampleŌĆØ, Chemosphere, 2015, 137, 198-206.

18. K. N├Čdler, O. Hillebrand, K. Idzik, M. Strathmann, F. Schiperski, J. Zirlewagen, and T. Licha, ŌĆ£Occurrence and fate of the angiotensin II receptor antagonist transformation product valsartan acid in the water cycle - A comparative study with selected ╬▓-blockers and the persistent anthropogenic wastewater indicators carbamazepine and acesulfameŌĆØ, Water Research, 2013, 47, 6650-6659.

19. K. S. Diamanti, N. A. Alygizakis, M.-C. Nika, M. Oswaldova, P. Oswald, N. S. Thomaidis, and J. Slobodnik, S, ŌĆ£Assessment of the chemical pollution status of the Dniester River Basin by wide-scope target and suspect screening using mass spectrometric techniquesŌĆØ, Analytical and Bioanalytical Chemistry, 2020, 412, 4893-4907.

20. N. A. Alygizakis, H. Besselink, G. K. Paulus, P. Oswald, L. M. Hornstra, M. Oswaldova, G. Medema, N. S. Thomaidis, P. A. Behnisch, and J. Slobodnik, A, ŌĆ£Characterization of wastewater effluents in the Danube River Basin with chemical screening, in vitro bioassays and antibiotic resistant genes analysisŌĆØ, Environment Intternational, 2019, 127, 420-429.

21. I. Pantelaki, and D. Voutsa, ŌĆ£Organophosphate flame retardants (OPFRs): A review on analytical methods and occurrence in wastewater and aquatic environmentŌĆØ, Science of The Total Environment, 2019, 649, 247-263.

22. S. Lee, H. Cho, W. Choi, and H. Moon, ŌĆ£Organophosphate flame retardants (OPFRs) in water and sediment: Occurrence, distribution, and hotspots of contamination of Lake Shihwa, KoreaŌĆØ, Marine Pollution Bulletin, 2018, 130, 105-112.

23. T. A. Slotkin, S. Skavicus, H. M. Stapleton, and F. J. Seidler, A, ŌĆ£Brominated and organophosphate flame retardants target different neurodevelopmental stages, characterized with embryonic neural stem cells and neuronotypic PC12 cellsŌĆØ, Toxicology, 2017, 390, 32-42.

24. W. Technology, C. Schaffner, and H.-P. E Kohler, Giger, C, ŌĆ£Benzotriazole and tolyltriazole as aquatic contaminants. 1. Input and occurrence in rivers and lakesŌĆØ, Environmental Science and Technology, 2016, 40 (23), 7186-7192.

25. G.-H. Lu, N. Gai, P. Zhang, H.-T. Piao, S. Chen, X.-C. Wang, X.-C. Jiao, X.-C. Yin, K.-Y. Tan, and Y.-L. Yang, ŌĆ£Perfluoroalkyl acids in surface waters and tapwater in the Qiantang River watershedŌĆöInfluences from paper, textile, and leather industriesŌĆØ, Chemosphere, 2017, 185, 610-617.

26. L. Zhao, P. W. Folsom, B. W. Wolstenholme, H. Sun, N. Wang, and R. C. Buck, ŌĆ£6:2 Fluorotelomer alcohol biotransformation in an aerobic river sediment systemŌĆØ, Chemosphere, 2013, 90, 203-209.

27. Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development, OECD Portal on Perfluorinated Chemicals, www.oecd.org/ehs/pfc, 2016

28. ņĄ£ņØĆĻ▓Į, ļéśņ¦äņä▒, ņĪ░ņśüļŗ¼, ņåĪĻĖ░ļ┤ē, ņØ┤ņłśņśü, ņäØĻ┤æņäż, "Ļ│╝ļČłĒÖöĒÖöĒĢ®ļ¼╝ņØś ĻĘ£ņĀ£ ļ░Å ņé░ņŚģņĀü ņÜ®ļÅäņŚÉ ļīĆĒĢ£ ĒÖöĒĢÖ ĻĄ¼ņĪ░ņĀü Ļ│Āņ░░." Textile Coloration and Finishing, 2016, 28(3), 134-155

- TOOLS