과불화화합물(PFASs)의 지속적 영향에 대한 국제적 규제 및 연구동향

Global Performance, Trends, and Challenges for Assessment and Management of Per- and Polyfluoroalkyl Substances (PFASs): A Critical Review

Article information

Trans Abstract

Per- and polyfluoroalkyl substances (PFASs) are a large and complex group of thousands of synthetic chemicals with different properties such as strong acidity, high surface activity at very low concentrations, high chemical stability, and water and oil repellency. Many PFASs have been used in various industrial and consumer applications based on the desired functionality and production capability, and have consequently emerged as pervasive environmental contaminants of major concern. Recognition that several PFASs are transported globally, bioaccumulate, and exert multiple adverse effects on environmental quality and health has led to their regulation and ultimate phase-out. Despite decades of global management and research on PFAS, fundamental obstacles still remain in addressing worldwide contamination by these chemicals and their associated impacts on environmental quality and human health. Here, we reviewed the global issues, major barriers, and challenges that must be addressed to remedy the “PFAS problem” from scientific, technological, and policy perspectives. A comprehensive review of the latest scientific research and recent legislative developments regarding PFAS will improve the assessment and management of the numerous PFAS on the market in the near future.

1. 서 론

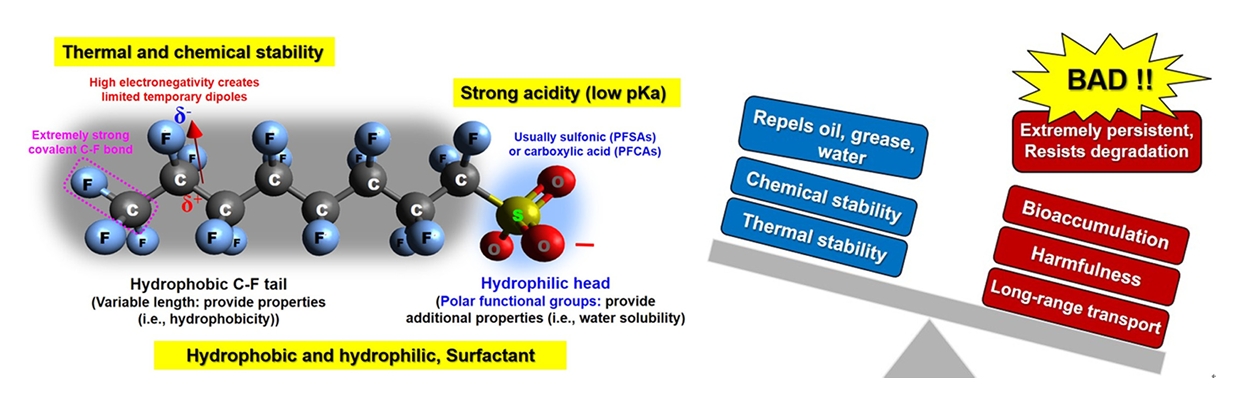

과불화화합물(Per- and poly-fluoroalkyl substances, PFASs)은 탄소와 불소로결합된 합성 불소화화합물로써, 적어도하나 이상의 Fluorinated methyl(-CF3) 또는 methylene (-CF2-)이 포함된 그룹형 화학물질로 정의될 수 있다. 탄소와 불소의 강한 공유결합과 강한 전기음성도의 화학적 구조는 친수성 및 소수성의 성질과 높은 표면활성, 화학적 또는 열적 안정성 등과 같은 이화학적 특성을 갖게 하였다[1]. 이런 독특한 특성으로, 1940년대 후반부터 다양한 제품(예: 화장품, 재조합 발포, 식품 접촉 재료, 가정용 제품, 잉크, 의료기기, 석유 생산, 광업, 농약 제제 및 섬유, 가죽및의류) 및응용분야에널리 사용되어왔다[2]. 하지만 과불화화합물의 안정성은 환경 내에서 분해 저항성이 높아 오랫동안 잔류하게 되어 전지구적으로 이동이 확대되었고, 생물체 내의 높은 농축과 독성으로 생물학적 장애를 일으키게 되었다(Fig. 1). 이에 따라, 1990년 후반부터 일부 과불화화합물(과불화옥탄산(Perfluorooctanoic acid, PFOA)과 과불화옥탄술폰산(Perfluorooctane sulfonate, PFOS), 과불화헥산술폰(Perfluorohexane sulfonic acid, PFHxS)과 그 전구체가 잔류성 유기오염물질(Persistent organic pollutants, POPs) 로써 전 세계적으로 주목을 받게 되었고, 이후로 국제적인 금지와 단계적 규제물질로 지정되었다[3]. 하지만 최근 국외 연구 보고서에 따르면 이미 사용되고 있는 과불화화합물의 종류는 2,060여 개이며, 최소 3,000개의 과불화화합물이 존재하고 있는 것으로 확인하였다. 이 중에는 규제되고 있는 과불화화합물(예, PFOS, PFOA 또는 그 전구체)과 구조적으로 유사한 신규 대체물질들이 포함되어 있으며, 이들 생산 및 사용량은 년간 10톤 이상인 것으로 나타났다 [1]. 더욱이, 고해상도 질량분석기술의 개발은 과불화화합물의 종류와 검출범위를 확장시키는데 기여하였고, 이에 따라 과불화화합물의 종류는 더욱 복잡하고 보다 큰 범위의 그룹 물질로 이루어진 것으로 밝혀졌다. 이와 같이, 과거의 과불화화합물 사용과 잔류, 그리고 현재 대체물질로 제조 및 생산되고, 새롭게 검출되고 있는 다양한 신규 과불화화합물, 앞으로 이들의 환경내 잔류 가능성, 이 모든 시나리오에 의해 현재 과불화화합물은 일명 ‘영원히 남는 화학 물질(Forever Chemicals)’ 로 불리고 있다. 이에 따라 국제적으로 기존 개별 화합물 중심의 위해성 평가와 규제 패러다임에 대하여 혁신적 변화의 필요성이 제시되었다. 최근 유럽집행위원회(European Commission)에서는 ‘지속가능성을 위한 EU 화학전략(European Commission’s Chemicals Strategy for Sustainability)’으로 과불화화합물에 대해 ‘필수사용개념(Essential-Use Concept)’을 도입하고 단계적 폐지를 위한 ‘필수적 사용(Essential)’, 및 ‘비필수적 사용(Non-essential)’에 관한 논의가 진행 중에 있다[4,5]. 하지만, 필수적 사용개념을 구현하려면 과불화화합물의 현재 사용량과 대안 가용성, 적합성 및 독성에 대한 충분한 자료와 이해가 필요하며, 대체물질로 사용되는 과불화화합물의 성능 및 독성과 사용에 대한 필요성이 정당화되어야 할 것이다. 뿐만 아니라, 대체물질의 개발과 생산에 따른 이들 물질의 환경적 위험성 평가와 잠재적 관리 조치에 대한 노력 또한 필요할 것이다[6].

따라서 본 연구에서는 1940년대 이후 국제적으로 널리 사용되고 있는 과불화화합물과 신규 대체물질의 환경유해성 평가와 관리 패러다임을 모색하기 위해서 국제적인 연구 동향 및 규제 방향을 검토하였다. ‘과불화화합물 문제(PFASs problem)’를 해결하기 위해 국제적으로 언급되고 과제와 한계점이 무엇인지 파악하고, 과학, 기술 및 정책적인 관점에서 이를 해결할 수 있는 방안에 대한 자료를 제공하고자 한다.

2. 과불화화합물의 종류, 규제 및 대체물질 사용

과거 과불화화합물의 광범위한 사용과 신규 대체물질의 개발, 미량물질 분석기술의 발전으로 현재 과불화화합물은 그 그룹과 종류가 급격하게 증가되고 있다[7,8]. 이와 같은 연구결과에 따라, 그간 ‘과불화화합물 세계(PFAS world)’에 대해 정확하게 이해하지 못하고, 알려진 과불화화합물이 과소평가 되고 있을 가능성이 높다는 것에 대해 인지하게 되었다. 이로 인해, 최근 신규 과불화화합물 및 대체물질과 관련된 학술연구, 규제 및 관리 방안은 국제적으로 큰 관심을 받게 되었다. 그간의 국제적 관심에 대한 현황 및 동향은 아래와 같다.

2.1. 과불화화합물 종류의 확대

지난 80년 동안 과불화화합물은 다양한 제품과 응용분야(예: 화장품, 재조합 발포, 식품 접촉 재료, 가정용 제품, 잉크, 의료기기, 석유 생산, 광업, 농약 및 섬유, 가죽 및 의류 등)에 광범위하게 사용되어왔다. 이들 제품 중에는 알려지지 않은 과불화화합물과 의도하지 않게 포함된 과불화화합물이 불순물로써 존재하고 있을 것으로 추측되기도 하였다. Place and Field (2012) [9]는 수성막포소화 약제(Aqueous Film Forming Foam, AFFF)에서 10개의 과불화화합물 분류를 검출하였지만, 이들 과불화화합물이 의도되어 포함된 과불화화합물인지, 잔류성으로 인해 변환된 중간체인지, 생산 중에 형성된 부산물 또는 분해 부산물인지에 대한 구분을 명확하게 하지 못하였다. 이는 과불화화합물이 제품생산 과정에서 다양한 원인들로 인해 그 종류가 확대될 수 있음을 보여주고 있는 결과로 해석될 수 있었다. 따라서, 우선 과불화화합물의 신뢰성 있는 제어와 관리를 위해서는 현재 사용되고 있는 과불화화합물의 종류를 정확하게 파악하고 그룹화하여 보다 체계적인 분류과정이 필요한 것으로 제안되고 있다. 스웨덴 화학물질청(Swedish Chemicals Agency)은 글로벌 시장에 존재하고 있는 과불화화합물의 종류는 이미 잘 알려진 긴 사슬의 과불화화합물을 포함하여 약 2,060개가 존재하고, 최소 3,000여개 이상이 있을 것으로 추정하였다[2]. 국제경제협력개발기구(Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development, OECD)에서는, 2019년까지 4,700개 이상의 과불화화합물이 글로벌 시장에 출시되었고, 130개 이상 분야에서 총 750개 이상의 과불화화합물이 검출되고 있는 것으로 보고하였다[10,11] (Table 1). 또한 유럽연합 화학물질등록 평가제도(Registration, Evaluation, Authorization and Restriction of Chemicals, REACH)에 등록되었거나 2019년 CLP 분류 및 표시 목록에 포함된 과불화화합물, 그리고 OECD/UNEP (United Nation Environment Programme)목록에 등록된 과불화화합물의 종류는 최대 9,000개 이상인 것으로 추정하였다. 2020년 미국 환경청(United States Environmental Protection Agency, US. EPA)에서는 CAS(Chemical Abstracts Service)에 등록된 과불화화합물의 종류는 6,330개 이상인 것으로 파악하였고, 화학구조로 표현된 과불화화합물은 5,264개인 것으로 확인하였다[12]. 최근, 2022년에는 12,034개의 과불화화합물이 포함되어진 것으로 나타났다.

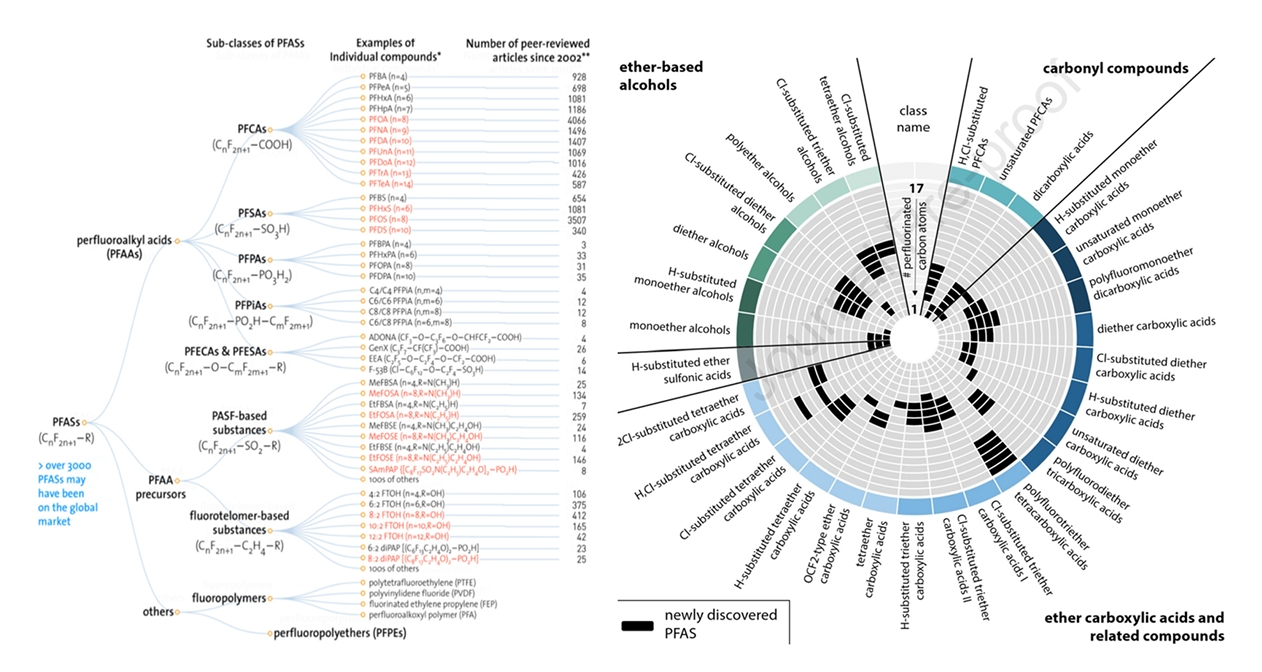

뿐만 아니라, 고도화된 미량 분석기술의 개발은 다양한 과불화화합물을 선별하고 식별할 수 있게 되었고, 과불화화합물의 종류를 확대하는데 큰 기여하게 하였다. 최근 고해상도 질량분석(High-Resolution Mass Spectrometry, HRMS)을 기반으로 한 분석 결과, 플루오로폴리머(Fluoropolymer)와 수성막포소화약제로 오염된 토양과 전자제품 제조공정에서 배출되는 폐수 및 유기 폐기물에서 알려지지 않은 과불화화합물의 종류가 검출되어졌다[8]. 새롭게 검출된 과불화화합물은 최소 87개의 에테르 구조로 750개 이상인 것으로 확인되어졌다 (Fig. 2). 전자 제조업체의 폐수에서는 카르복실기를 갖는 흔하지 않은 에테르 구조의 그룹을 포함하여 6개의 그룹, 21개의 동족체(Homologues)가 존재하고 있는 것으로 밝혀졌다[13]. Glüge et al. (2022) [6]는 200개 이상의 적용범위에 대하여 체계적인 고찰을 통해 과불화화합물의 오염을 추적하는데 기초적인 자료를 제공하였다. 또한 고해상도 질량분석 및 불소질량 균형 분석연구는 생물학적 및 비생물적 변환 경로를 규명하는데 기여하였고, 새로운 중간 변환 과불화화합물과 분해 부산물을 예측하는데 큰 기여를 하였다[8,11]. 초기 생애단계의 제브라피쉬에서 74개 과불화화합물의 대사 경로는 구조 의존성이 높은 것으로 밝혀졌고, 수성막포소화약제에 노출된 쥐에서는 일련의 설포아마이드 다이머(Sulfonamide dimer)의 대사물질이 발견되기도 하였다. 불소질량균형 연구에서는 기존의 고해상도 질량분석으로 정량화 할 수 없는 유기 플루오린화물을 측정하여 새로운 과불화화합물을 검출하였다. 해양 포유류 샘플에서는 30-75%의 미확인 추출가능 유기불소화합물(Extractable Organic Fluorine, EOF)에서 37개의 새로운 과불화화합물을 검출하였다[14].

Emerging awareness and emphasis on PFAS occurrence in the environment [56]; (left) PFAS discoveries (as claimed by the authors, confidence level ≥ 3) in selected studies that underline the structural diversity of the novel (tentatively) identified PFAS. The outer colored circle represents the PFAS class and the inner grey circles illustrate the homologues within the respective class having 1 to 17 perfluorinated carbon atoms. Newly discovered PFAS since 2019 are marked in black (n = 87), but these only represent a subset since this review only considered selected studies [8]; (right) “Family tree” of PFASs, including examples of individual PFASs and the number of peer-reviewed articles on them since 2002 (most of the studies focused on long-chain PFCAs, PFSAs and their major precursors.) * PFAS in RED are those that have been restricted under national/regional/global regulatory or voluntary frameworks, with or without specific exemption, Risk reduction approaches for PFASs. ** The numbers of articles (related to all aspects of research) were retrieved from SciFinder on Nov.1, 2016 [7]

2.2. 과불화화합물의 국제적 규제 현황

과불화화합물은 하나 이상의 퍼플루오로알킬기를 포함하는 합성 화학물질로써, 1947년 3M사에 의해 생산되기 시작하였고, 1951년 DuPont사에서 Fluoropolymer의 제조로 사용한 이래 지난 반세기 동안 전 세계적으로 다양한 제품으로 생산 및 사용되어져 왔다. 하지만, 3M사의 유기 불소계 화합물 제조 공정을 하는 근로자 혈액 내에서 과불화옥탄술폰산(PFOS)이 검출됨에 따라 최초로 과불화화합물의 독성 문제가 제기되어, 50년 이상 생산해 온 제품을 중단 및 수거를 하게 되었다. 이 후 과불화화합물은 국제적인 관심을 받게 되었고 관련된 연구가 수행되어져 왔다. 특히, 전지구적으로 대기, 물, 토양, 생물 중에서도 과불화화합물이 고농도로 잔류하고 있는 것으로 확인되었고, 이 중 PFOS와 PFOA은 독성이 높은 것으로 제시되었다. 특히, 동물을 이용한 생체 위해성 평가에서 과불화화합물은 혈액 내의 단백질을 응고시키고, 호르몬의 feed-back 시스템에 영향을 주며, 간독성, 발암, 발육장애, 임신장애 및 태아기형, 면역체계에 영향을 미치고, 성적인 발달을 지연시키며, 콜레스테롤 수치를 상승시켜 심장병이나 심장마비를 유발하는 것으로 보고되었다. 뿐만 아니라, 인체 내의 지방질에는 축적이 되지 않지만 혈액 단백질과 결합하는 특성으로 인해 간이나 콩팥에 축적되는 것으로 알려져 있다[15-18]. 2003년과 2004년의 연구결과에 따르면 미국 시민 99.7%의 혈액 내에서 평균 4 µg L-1의 과불화화합물이 검출되었고, 알래스카에서 서식하는 북극곰에서도 과불화화합물이 검출되어, 동물과 인체 내에 장기간 축적되고 있는 것으로 나타났다[3,19].

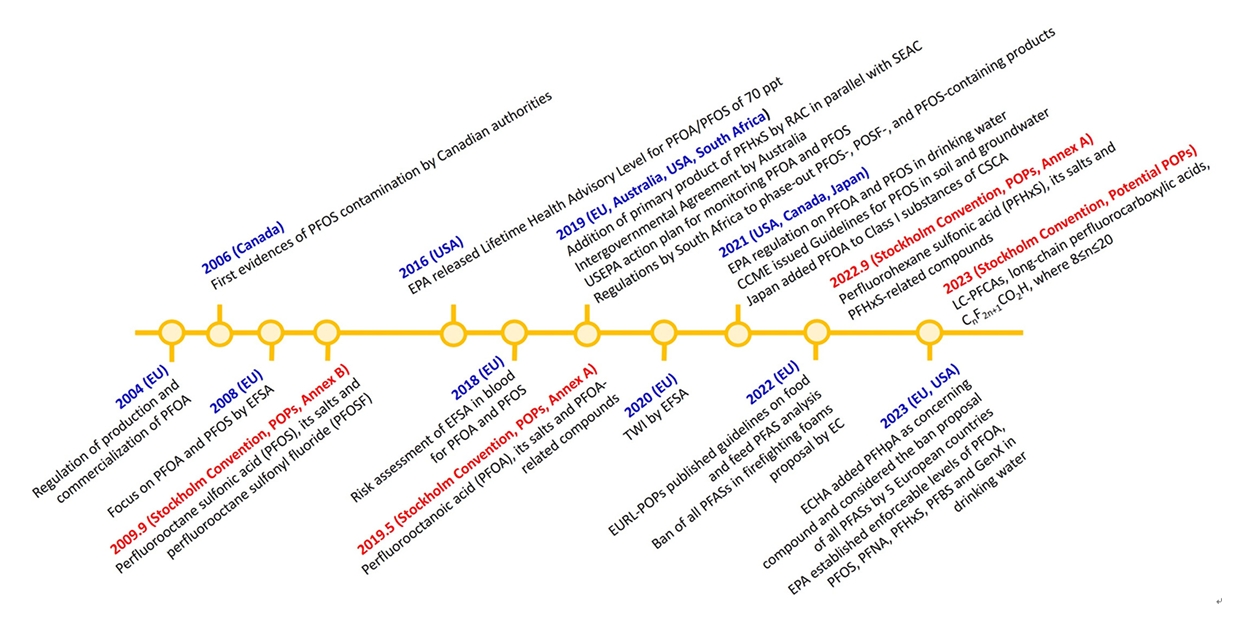

이에 따라, 2009년 9월 스톡홀름 협약 당사국총회에서 과불화옥탄술폰산, 그 염류 및 과불화옥탄술포닐플로라이드(Perfluorooctane sulfonic acid (PFOS), its salts and perfluorooctane sulfonyl fluoride (PFOSF))는 POPs 물질로 Annex B에 등재된 규제 대상물질로 등재되었으며, 이 후 과불화옥탄산과 그 염류, 과불화옥탄산 관련 화합물(Perfluorooctanoic acid (PFOA), its salts and PFOA-related compounds)은 제9차 당사국총회(2019년 5월)에서 Annex A에 등재되어 규제되고 있다. 최근 2022년 9월에 개최한 총회에서는 과불화헥산술폰산과 관련된 화합물(Perfluorohexane sulfonic acid (PFHxS), its salts and PFHxS-related compounds)이 Annex A에 신규로 추가되어 규제물질로 등재되었다. 현재에는 긴 사슬의 과불화카르복실산(LC-PFCAs, long-chain perfluorocarboxylic acids, CnF2n+1CO2H, where 8 ≤ n ≤ 20)이 POPs물질로써 규제 후보 물질로 검토 중에 있다[20](Fig. 3).

유럽화학물질청(European Chemicals Agency, ECHA)은 독일과 스웨덴 당국의 긴 사슬 과불화카르복실산(C9-C14 PFCA), 그 염 및 전구체의 사용제한을 제안하였고, 유럽 위원회의 결정에 따라 2023년 2월부터 유럽연합/유렵경제지역(EU/EEA, European Union/European Economic Area)에서 그 사용이 제한되어지고 있다. 독일에서는 Undecafluorohexanoic acid (PFHxA), its salts and related substances에 대해 추가적으로 제한하는 것을 제안하였다. 2021년 12월 유럽화학물질청의 과학 위원회은 이 제안을 평가하였고, 유럽연합 국가와 함께 적절한 시기에 제한 사항을 최종 결정할 것이라 밝혔다. 독일, 덴마크, 네덜란드, 노르웨이, 스웨덴 당국은 2019년 12월 환경위원회에서 발표한 성명을 뒷받침하여 광범위한 과불화화합물 사용을 포괄적인 제한하자는 내용으로, 2023년 1월에 유럽화학물질청에 그 제안서를 제출하였고, 현재 유럽화학물질청의 과학 위원회가 이를 평가하고 있다. 뿐만 아니라, 유럽화학물질청은 2022년 1월 소방용 폼에 사용되는 과불화화합물에 대해서도 제한하기로 제안하였으며, 2023년 6월에는 EU REACH 규정의 Annex XVII에서 Undecafluorohexanoic Acid, its salts, and related substances을 화장품을 포함한 다양한 적용분야에서 사용 금지하도록 하는 내용으로 무역기술장벽 통보문(TBT, Technical Barriers to Trade)을 통해 발표하였다. 한편, 3M은 과불화화합물의 생산을 단계적으로 폐기가 시작하였고, 2024년 12월에는 최대 23억 달러를 투자하여 2025년까지 과불화화합물의 생산을 중단하기로 하였다.

2.3. 짧은 사슬 대체물질과 긴 사슬 과불화화합물의 사용

긴 사슬 과불화화합물(PFOA/PFOS)이 단계적으로 폐지됨에 따라, 경제적/용도적 관점에서 그룹 내 다른 화합물로의 대체가 우선적으로 진행되었고, 신규 대체물질의 개발이 촉진되어졌다. 즉, C8 기반 PFOA/PFOS의 국제적인 사용 규제는 짧은 사슬 과불화화합물 형태의 신규 대체물질(즉, 탄소가 7개 미만의 대체물질)과 C10-C13의 긴 사슬 과불화화합물의 형태로 대체되어 사용되어지고 있다[21]. 짧은 사슬의 과불화화합물 대체물질로는 GenX, ADONA, F53B가 널리 사용되고 있다. GenX는 헥사플루오로프로필렌 옥사이드 이량체산(Hexafluoropropylene oxide dimer acid, HFPO-DA)과 그 암모늄염을 주성분으로 하는 짧은 사슬 과불화화합물의 상품명이며, ADONA (Dodecafluoro-3H-4,8-dioxanonanoate)는 플루오로폴리머 제조에 사용되는 상품명으로써 이 둘의 성분은 PFOA의 대체물질로 사용되고 있다. F53B (6:2 chlorinated polyfluoroethersul-fonic acid/9-chlorohexadecafluoro-3-oxanone1-sulfonic acid/6:2 Cl-PFESA/9Cl-PF3ONS)는 PFOS의 대안으로 제조되어 여러 전기 도금 업체에 의해 사용되고 있는 것으로 나타났다[6]. 이런 대체물질의 과불화화합물은 짧은 사슬길이와 알칼리 에테르 치환으로 큰 수용성의 특성을 갖기 때문에 수질으로 이동이 클 것으로 보고되고 있다[22]. 반대로, 탄소 사슬 길이가 9~21인 긴 사슬의 과불화카르복실산(PFCA)과 그 염(CnF2n+1CO2H, 8≤n≤20) 또한 대체물질로써 사용되고 있다. 이 중 탄소 사슬 C9의 PFCA의 암모늄염은 계면활성제 적용 및 플루오로 폴리머 제조에 사용되는 것으로 나타났다[21]. 또한 코팅 제품, 직물/카펫 프로텍터, 직물 함침제 및 소방 폼을 포함하는 다양한 적용에 사용되었다. 이런 긴 사슬의 과불화카르복실산은 짧은 사슬의 과불화화합물에 비해 환경에서의 지속성, 생물학적 축적, 장거리 이동성이 크기 때문에 토양 또는 농작물, 지표수 및 지하수에서 고농도로 검출되고 있다. 또한 간독성, 발달/생식 독성, 면역독성, 갑상선 독성 및 기타(예: 심혈관, 대사, 신장 독성) 질환이 긴 사슬의 과불화카르복실산의 노출과 높은 상관성이 있는 것으로 나타났다[23,24].

3. 과불화화합물 문제 해결의 한계

과불화화합물은 잠재적으로 ‘영원히 남는 화학물질(Forever Chemicals)’로 인식되고 있다. 하지만, 과불화화합물의 거동과 이동, 생물학적 영향, 환경 배출에 관하여 20여 년간의 연구에도 불구하고, 여전히 ‘PFAS 문제’에 대한 효과적인 해결방안을 찾지 못하고 있는 실정이다. 이와 같은 어려움은 과불화화합물 종류의 다양성, 분석의 어려움, 과불화화합물을 생산 및 제조하는 사용 및 배출량의 자료 부족 등에 의한 것이다. 따라서 과불화화합물의 국제적인 규제 및 단계적인 금지를 위해서는 앞서 해결해야 할 문제점을 파악하고, 과학, 기술 및 정책적인 관점에서 해결방안이 제시되어야 할 것으로 판단된다. 최근 국제적으로 과불화화합물 문제를 해결하기 위해 논의되고 있는 한계점에 대해 고찰하였다.

3.1. 과불화화합물의 생산과 사용량, 배출원 파악의 한계

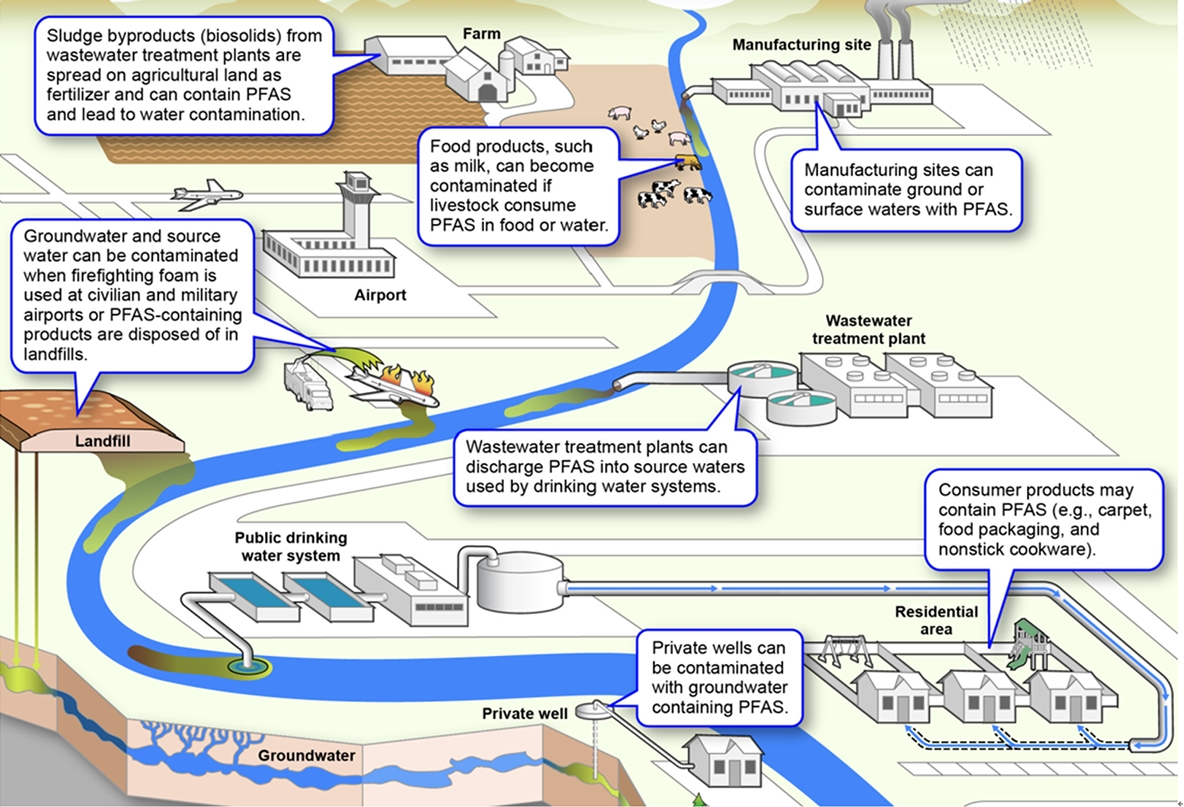

유럽연합의 경우, 2020년에 과불화화합물은 14만~31만 톤이 제품으로 시장으로 유입되었을 것으로 추산하였고, 여러 분야의 경제성장으로 인해 기존의 시나리오 보다 더욱 증가할 것으로 예측하였다. 또한 매년 75,000톤이 유럽 환경에 배출되고 있는 것으로 보고되었고[25], 특별한 규제로 제한되지 않는 한 향후 30년 동안 유럽연합 환경내로 약 450만 톤이 배출될 수 있을 것으로 추정하였다. 하지만, 분야별 과불화화합물의 배출량은 과거 및 현재에 생산되고 있는 양에 대한 정보수집의 한계로 인해 이를 추정하는 연구는 매우 어려운 실정이다. 이는 각국의 규제 기관이 해당지역에서 규제물질에 대하여 생산 및 사용에 대한 물질정보를 수집, 운영 관리하고 있지만, 이들 정보에 대해서는 대부분 공개하고 있지 않다. 뿐만 아니라, 새로운 용도로 적용되고 있을 경우는 문서화되고 있지 않는 실정이다[26]. 일부 국가의 규제기관(예, US. EPA)에서는 독성물질 배출량을 수집 및 공개하고 있으나 산업부문, 소규모기업, 영업비밀 등의 면제사항으로 인하여, 세부적인 수준의 정보는 여전히 부족한 실정이다. 뿐만 아니라, 과불화화합물은 과거부터 많은 양이 사용되었고, 현재 그 종류만 약 10,000개 이상이 사용되고 있으며, 생산 및 제조과정 다양한 전구체의 변환으로 인해 정확한 양의 사용량 및 배출량 추정하기는 현실적으로 매우 어렵다[27]. 더욱이 산업체에서 불순물로 포함된 과불화화합물은 그 종류와 생산 및 소비량, 배출량 관련 정보를 추적하기 매우 힘든 실정이다. 그리고 환경 내에서 과불화화합물은 시간이 지남에 따라 전구체의 분해와 변환과정으로 인하여 다양한 과불화화합물로 변화되고 이들이 얼마나 많은 양으로 환경내에 잔류하고 있는지에 대한 자료는 거의 전무하다[7]. 또한 수만개의 과불화화합물 개별적으로 이화학적 특성으로 인하여 환경내에서의 이동과 거동에 차이가 있다. 예를 들어, 과불화화합물을 성분으로 하는 상업용 소방폼 계면활성제는 과거에서부터 현재까지 많은 양이 제조 및 사용되고 있으며, 환경 내에 노출되었을 때 과불화화합물의 조성 변화로 인하여 오염농도와 노출범위를 특정하기에 한계가 있다(Fig. 4). 이런 과불화화합물 배출량 자료의 부재로 인해 유해한 영향이 노출될 때 또는 그 이후로도 인체 건강상 및 환경독성 영향평가의 한계가 있을 것이다(Ng et al., 2021). 따라서, 신뢰성 있는 배출원 자료를 구축하고, 환경(토양, 수질, 대기 등)에서의 거동과 이동을 파악하여, 건강상의 노출 및 위험성 평가 관한 체계적 연구가 선행되어야 할 것이다. 마지막으로, 산업체는 제품의 화학적 안전성을 객관적인 자료로 공개하고 제조화되는 과정에서 과불화화합물의 존재 여부를 제시해야 할 것이다. 더불어 이에 대한 정보와 보고과정을 체계화하고, 대중의 관심과 규칙, 규정이 필수적일 것이다. 2021년 6월에 미국 환경청은 과불화화합물을 제조하는 소규모 사업체까지 사용량 등을 보고하도록 새로운 규정으로 제안하였다[28]. 하지만 이 규정은 여전히 생산에만 제한되어 있어 제품의 과불화화합물 배출에 따른 자료 활용으로는 어려움이 있는 것으로 지적되었고, 제품 및 환경 배출에서 과불화화합물의 발생과 영향을 확인하기 위해서는 모니터링 및 예측 모형 연구 등의 접근 방식이 더불어 포함되어야 할 것으로 제안되었다[26].

현재 과불화화합물이 사용되고 있는 분야는 불소중합체 생산의 중합 보조제, 소방폼 계면활성제, 크롬 도금 미스트 방지제, 직물·가죽·식품포장·화장품의 발수 및 발유제, 식물보호 제품, 살충제, 사료 첨가제, 의약품 및 페인트 보조제, 반도체 및 의료기기 부품생산 등이 적용되고 있으며, 1,400개 이상의 과불화화합물이 200개 이상의 분야에 포함되어 있는 것으로 나타났다[29]. 하지만 구체적인 과불화화합물을 취급 및 배출 산업에 대한 체계적인 목록과 배출원의 위치 정보, 또한 오염된 매체의 오염원으로써 공간적 분포 등의 자료가 부족한 실정이다. 따라서 과불화화합물의 농도가 높은 지역의, 환경 매체를 파악하고 효과적으로 관리하기 위해, 과불화화합물 이동을 예측하는 모델 개발의 필요성이 제안되고 있다. 예를 들어 지리정보시스템(GIS)을 사용하여 공간적 데이터를 공유하고, 다양한 매체(예: 공기, 물, 토양, 퇴적물)를 모니터링하고 오염지점을 구별하고 환경내에서의 거동 및 이동 예측 모델을 통해 누락된 배출원 또는 매체영역을 예측하여야 할 것으로 제안하였다[24,26,30]. 이와 같은 과불화화합물의 오염과 규모 등의 자료는 국가 차원의 인식을 높이는 데 중요한 자료가 될 것이다.

3.2. 과불화화합물 분석기술 확대의 한계점

최근의 모니터링 연구에서는 인간과 환경매체에서 화학적 구조가 유사한 신규 과불화화합물의 비율이 증가되고 있는 결과를 보여주고 있다. 이는 다양한 과불화화합물의 사용으로 인한 것, 뿐만 아니라, 미량분석 기술의 개발로 인하여 알려지지 않은 과불화화합물이 검출되어진 것으로 볼 수 있다. 또한, 개선된 분석기술은 향후 알려지지 않은 새로운 물질들을 추가적으로 검출할 수 있을 것으로 기대하고 있다.

일반적으로 과불화화합물은 액체 크로마토그래피(Liquid Chromatography, LC), 전자분무 이온화(Electrospray Ionization, ESI)와 고해상도 질량 분석기(High Resolution Mass Spectrometry, HRMS)의 결합된 장비로 분석되어진다. 뿐만 아니라, 초임계 유체 크로마토그래피(Supercritical Fluid Chromatography, SFC) 또는 친수성 상호작용 액체 크로마토그래피(Hydrophilic Interaction Liquid Chromatography, HILIC)와 같은 상호 보완적인 분리기술 장비로 초단체인 과불화화합물(Ultra-short chain PFASs)을 분석할 수 있게 되었다[31]. 인간 간의 지방산 결합 단백질과 결합하는 과불화화합물은 HRMS 기반 분석과 통합된 크기-배제 컬럼 용해(Size-Exclusion Column Coelution, SECC)에 의해 확인될 수 있다[32]. Young et al. (2022) [33]은 사중극자 시간비행형 질량분석기(Quadrupole Time-of-Flight, QTof)와 오비트랩(Orbitrap) 질량분석기에 더해 21 테슬라 푸리에 변환 이온 사이클로트론 공명-질량 분광기(Fourier-Transform-Ion Cyclotron Resonance-Mass Spectrometer, FT-ICR-MS)를 사용하여 복잡한 수성 필름포밍 폼에서의 다양한 과불화화합물을 새롭게 검출하였으며, 높은 질량 분해능, 정확도, 동적 범위의 분석 가능성을 보여주었다. 또한 Dodds et al. (2020) [34]은 이동성 유도 충돌 단면(Mobility-Derived Collision Cross Section, CCS) 값을 사용하여 PFOA 및 PFOS와 같은 밀접하게 용출되는 구성 이성질체를 분리하고 특정 과불화화합물의 헤드그룹이 주어진 m/z에 대한 이동성 유도 충돌 단면값에 상당한 영향을 미친다는 것을 이용하여, 과불화화합물의 참조 정보를 사용하여 알 수 없었던 과불화화합물을 식별하였다.

이와 같은 분석기술의 새로운 개발은 환경 및 생물 시료에서 알려진 또는 알려지지 않은 과불화화합물을 검출하고 구별하는데 큰 기여를 하고는 있지만, 고도로 전문화된 기술인력이 필요하며, 오염원을 추적하기 위해 많은 시간이 소요된다. 그리고 알려지지 않은 과불화화합물이 식별되더라도 다양한 과불화화합물을 포함하여 평가하거나 관리 우선순위를 결정하는 체계는 여전히 해결해야 할 과제이다[26]. 뿐만 아니라, 다양한 환경매체 즉, 음용수, 하수 슬러지, 식품, 혈액, 지방 및 다양한 종류의 제품 및 혼합물에서 과불화화합물의 정성 및 정량 분석 결과의 신뢰성을 갖기 위해서는 표준화된 분석절차의 기준이 필요하며, 이는 향후 모니터링 방법 및 규정 제정에 중요한 부분이 될 것이다[35,36]. 마지막으로 개발도상국에서 분석기술을 이용할 수 있도록 신속하고 저비용의 효율적인 분석기술이 개발된다면, 개발도상국의 오염 농도와 분포가 높은 지역에서의 현재 알려지지 않은 과불화화합물의 환경내 이동과 거동에 대한 이해가 크게 향상될 것으로 기대하고 있다. 이를 위해, 분석기술 활용이 단순하고 저비용으로 과불화화합물을 검출할 수 있는 검증되고 표준화된 센서 개발이 필요하며[37-40], 지속적인 과불화화합물 연구 및 조사를 촉진하기 위해 분석 장비 기부 프로그램이 활성화되어야 할 것으로 제안되고 있다[41].

3.3. 과불화화합물 폐기물 관리의 한계점

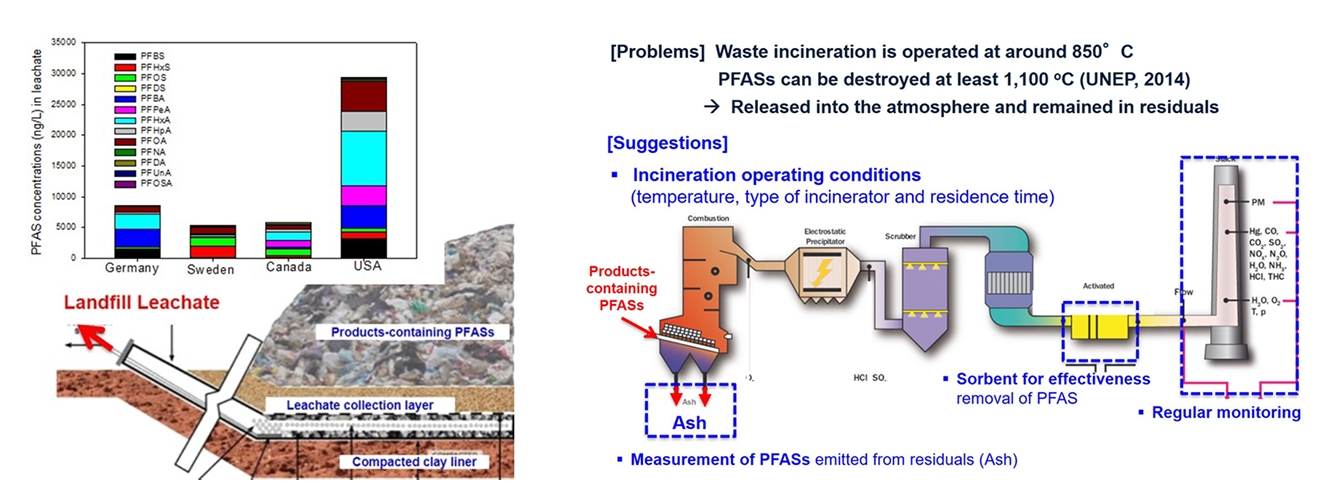

앞서설명한것처럼과불화화합물은섬유, 식품포장제, 개인 위생 및 가정 용품 등 다양한 제품과 제조과정에서 사용되어 왔고, 이후 제품 및 제조 부산물(슬러지, 폐수 등)에 잔류되어, 최종 매립되거나 폐수처리 되어진다. 이로 인해 매립지 내 과불화화합물은 침출수 등을 통해 주변 환경으로 이동하게 되어 대기, 수질 또는 토양오염으로 확대되어진다[26,42,43] (Fig. 5).

오염된 토양 및 수질에서 과불화화합물을 제거하기 위한 다양한 기술들이 개발되고 있으나 소요되는 에너지와 비용, 제거효율의 저감 등으로 현장적용에 어려움이 있는 것으로 보고되고 있다. 예를 들어, 흡착 또는 멤브레인을 통한 제거공정은 과불화화합물을 제거하기 위해 사용된 흡착제와 멤브레인을 처리해야 하는 추가적인 과정이 필요하지만 이에 대한 추가적인 해결책이 제시되고 있지 않은 실정이다. 대규모 수처리시설에서는 잔류성 및 수용성을 갖는 과불화화합물을 제거를 위해 고도처리기술(예: 역삼투압)을 적용할 수 있지만, 설치 및 유지보수 비용이 많은 들기 때문에 소규모시설에 적용하기에는 현실적으로 한계가 있다[44-48]. 더욱이 수처리 시설에서 발생되는 최종 부산물 또한 과불화화합물이 농축되어 잔류하고 있기 때문에 추가적인 처리가 필요하다. 일반적으로 수처리에서 발생되는 고상 부산물과 기타 폐기물은 소각과정으로 처리되지만, 과불화화합물의 탄소-불소 결합의 높은 안정성으로 인하여 완전연소를 위해서는 큰 비용과 에너지가 필요하다. 즉, 일반적인 도시 폐기물 소각로의 소각온도는 850oC에서 적어도 2초 동안 소각되므로 도록 설정되어 있지만, 과불화화합물의 완전연소를 위해서는 최소 1,000oC의 온도로 소각되어야 하므로 그 만큼의 에너지와 비용이 필요하게 된다[49,50] (Fig 5). 그러므로 과불화화합물 처리 한계점과 고비용을 감안할 때, 필수용도 사용의 경우를 제외하고 과불화화합물을 줄이는 것이 향후 처리에 있어 가장 효과적인 해결 방안일 것이다. 특히 필수용도의 경우에는 과불화화합물의 배출량이 최소화되도록 하고, 과불화화합물을 포함한 제품에 대해서는 제품에 그 내용을 표시하도록 제안되었다[26]. 이런 제안 사용 용도파악과 배출을 줄이는 데 효과적이며, 재활용 과정에서 과불화화합물 포함되어 있는 폐기물을 분리하여 처리할 수 있을 것이다. 기존 폐기물 문제를 해결하기 위해서는 예산과 연구를 통해 합리적인 비용으로 효과적으로 제거할 수 있는 기술(하이브리드 기술 등)을 개발하여야 한다[26]. 하지만 재배출을 방지하기 위한 입증된 기술과 전략이 마련될 때까지 대규모로 처리하는 기술을 테스트하는 것에 지양되어야 할 것이다.

3.4. 노출경로와 건강상 영향 파악의 한계

과불화화합물의 오염과 이에 대한 건강상의 영향을 어떻게 다뤄야 할지에 대한 문제는 여전히 해결해야 할 숙제이다. 대부분의 과불화화합물의 경우, 시간이 지남에 따라 환경과 생물에서 많은 양이 노출되고 있으며, 그 노출된 양이 얼만큼 축적될 것인지에 대한 정보는 거의 부족한 실정이다. 따라서 기존에 노출되고 있는 과불화화합물에 대한 잠재적 영향을 해결하고 향후 유사한 구조의 신규 과불화화합물의 광범위한 사용을 방지하기 위해, 측정된 노출양 (예, 혈액 내 특정 PFAS 농도)과 건강상의 영향과 연결해서 이해하여야 할 것이다[26]. 뿐만 아니라, 과 불화화합물의 이화학적 특성과 독성발현 기작과의 연관성을 기초로 한 건강상의 영향도 파악되어야 할 것이다. 하지만 과불화화합물 연구에서 가장 어려운 분야 중 하나는 인과 관계에 대한 증명이다[51]. 예를 들면, 과불화화 합물에 노출된 결과로 건강상의 문제가 있나? 또는 혈액 내에서 검출된 과불화화합물은 향후 질병을 유발할 것인가? 와 같은 경우이다. 이럴 경우가 증명된다면, 오염의 책임이 있는 당사자가 건강 및 복구 비용을 부담해야 하는 문제도 직면하게 될 것이다. 따라서 다양한 노출 경로를 가진 집단을 대상으로 하는 역학연구를 통해 노출과 영향 사이의 명확한 상관관계와 노출되는 정도와 건강상의 영향을 명확히 밝히는 과정이 필요할 것이다. 이런 과정을 위해서는 대체 신규 과불화화합물은 물론 전구체 및 분해 생성물을 대상으로 구조-활성관계 및 메커니즘 규명, 단일 노출 또는 혼합 노출에서의 독성평가, 분자 마커 또는 대사 지문을 이용한 과불화화합물의 노출 및 독성 평가 기술 등의 학문적 역학 연구가 수행되어야 할 것이다[26]. 또한 과불화화합물의 노출에 따른 독성 잠재력을 추정하려면 다양한 환경매체(예: 토양, 물, 공기)의 통합적인 데이터 수집과 질량균형 모델을 개발하고 객관적인 이동 경로를 추적해야 한다[21,52].

4. 결 론

21세기 이후 전 지구적으로 환경매체와 동물 등에서 과불화화합물의 검출이 증가되고 있는 것으로 나타났다. 또한 과불화화합물은 생체 내 장기 축적되며 생물학적 장애 및 독성을 일으킴에 따라 국제적 규제와 단계적 금지가 되고 있다. 국제적인 규제와 사용제한으로 인하여 최근 구조가 유사한 다양한 대체 과불화화합물이 개발 및 생산되었고, 다양한 용도로 광범위하게 사용되고 있어, 과불화화합물의 종류는 확대되고 있는 실정이다. 이와 더불어 고해상도 질량분석기술 발전으로 환경매체 및 동물/인간에서 규제물질 이외의 새로운 과불화화합물이 검출되어지고 있어, 그 종류가 급격하게 증가되고 있는 것으로 나타났다. 그리고 이들의 환경 내 높은 잔류로 인해 ‘영원히 남는 화학물질(Forever Chemical)’로 불리고 있다. 하지만 과불화화합물의 거동과 이동, 생물학적 영향, 환경 배출에 관한 20여년간의 연구에도 불구하고, 여전히 ‘PFAS 문제’에 대한 효과적인 해결방안을 찾지 못하고 있다. 각국에서는 환경 및 인체 노출을 최소화하기 위한 사회적인 과불화화합물 규제 방안을 논의하고 있다. 특히, 유럽에서는 단계적 폐지를 위한 비필수 사용개념과필수 사용개념을고려하고 있으며, 필수사용개념을 구현하기 위해 과불화화합물의 현재 사용량과 대안 가용성, 적합성 및 독성에 대한 자료, 대체물질로 사용되는 과불화화합물의 성능 및 독성, 대체사용에 대한 필요성 등을 기초로 구체적인 방법적 논의를 하고 있다.